A Response to: Leading Disruption & Decolonizing Our Institutions: Facing History & Ourselves

For those of us who make the commitment to learn more about the stories of the Indigenous people of Turtle Island, their past, the present and their future, we are stuck in a paradox. We have been called to recognize the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action specific to education, numbers 62 and 63.

Every board in Ontario has an Indigenous lead. I have had the great honour to learn alongside the lead in my former board who is an Anishinaabe Kwe for several years and she has introduced me to much learning and new friends. It is through these relationships that the deepest learning can happen.

At the same time, I know it is incumbent upon me, as an educator and as a settler to learn these stories, the truth, the ways of knowing and being, the worldview and in doing so, learn about the diversity of peoples, beliefs, and how I can be better in my role as an educator because of it. I must make the commitment to  ensure the students in my school and my own children learn about the residential schools, the treaties, the historical and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples. I can seek further connection to this learning by building intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect. As a school leader, I can participate in and seek opportunities for professional learning for my staff tied to truth and reconciliation. So when my friend told me about the opportunity to attend the session at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Leading Disruption & Decolonizing Our Institutions: Facing History & Ourselves, I jumped at the opportunity. There were several boards present with teams of educators from school to system level who were committed to the learning.

ensure the students in my school and my own children learn about the residential schools, the treaties, the historical and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples. I can seek further connection to this learning by building intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect. As a school leader, I can participate in and seek opportunities for professional learning for my staff tied to truth and reconciliation. So when my friend told me about the opportunity to attend the session at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Leading Disruption & Decolonizing Our Institutions: Facing History & Ourselves, I jumped at the opportunity. There were several boards present with teams of educators from school to system level who were committed to the learning.

So what is the paradox?

Since the session, I attended a conference where Robin DiAngelo spoke, the woman who coined the term, white fragility. She spoke directly to the white people in the room who she referred to as white progressives. She shared that she often receives a warning prior to speaking at these engagements that she is “speaking to the choir”. Many of us sit in the room and think about how we are so evolved and we begin to name our colleagues who should be here. This is a game that both white progressives and racialized people play. She explains that many of us who identify as white progressives cause harm because we see ourselves as different than “those white people” because “Look at me! I am here! I am different!” but she informs us, we are not different. We perpetuate our privilege, ignorance and fragility with our “good intentions”. I feel stuck. I begin to wonder that I am damned if I do and damned if I don’t. I cannot speak for but I must spend my privilege to claim to be a leader committed to social justice and Indigenous sovereignty.

DiAngelo explains that as white progressives, we set ourselves up as different by credentialing ourselves. I can list the books I have read, the podcasts I have listened to and even co-hosted, the events I have supported, the professional learning I have attended and championed. I can give you a list of speakers I have invited to my schools, books I have bought for my school’s library, memos I have written to staff and community, Indigenous owned and operated restaurants I have gone to and leaders and educators from Indigenous schools in the north with whom I have learned. I can list friends who are Indigenous educators, artists, leaders. I can give you a list of credentials that would impress most people who are white settlers. But for what?

I have been astounded by stories of resilience, stories filled with humour and discovered that my place is to listen, to bear witness. My encounters remind me how unaware we have been to the humanity of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The very act of writing this blog feels as though it is just not my place and yet I have been invited into this space.

On this day, at the Art Gallery of Ontario, we learned with Elder Garry Sault, an Ojibway Elder from Mississaugas of the Credit Nation who introduced himself first by what he referred to as his “slave name”. He then shared his Ojibway name, Ogazigay Heganin which means the two front teeth of a beaver which he claims is the reason he eats so much. This name is the name that holds meaning. He welcomed all of the  educators by singing a song with his drum and then exclaimed, “the doorway to understanding is now open”. This was an invitation to walk through the door and stand with, listen and to witness. He explains that the songs are a way that his people “commune with the creator” and the reverence in the room is palpable.

educators by singing a song with his drum and then exclaimed, “the doorway to understanding is now open”. This was an invitation to walk through the door and stand with, listen and to witness. He explains that the songs are a way that his people “commune with the creator” and the reverence in the room is palpable.

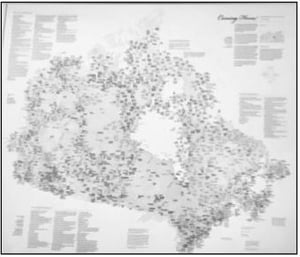

Facing History and Ourselves began and framed the day with a map, Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names, Canadian-American Center, University of Maine, which shows the land which we now call Canada with the many names and places prior to colonization. I am overwhelmed by the depth of diversity, the descriptive language in the naming, the sheer density. As my eyes wander the map I am struck by the richness as well as the tremendous loss at the hands of the colonizers who sought to destroy these great civilizations through both assimilation and genocide.

We entered into the gallery, J. S McLean Centre for Indigenous and Canadian Art and disruption lives here--this gallery which is curated by the AGOs first Indigenous curator, Wanda Nanibush, where works are described first in Anishinaabemowin to honour the land on which the AGO sits which is Mississauga Anishinaabe territory followed by the colonizer languages of English and French. The Inuit collection features texts in Inuktitut, along with English and French.

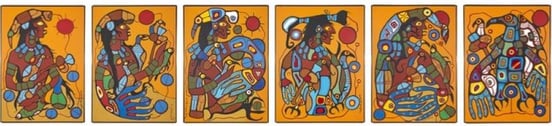

We learned from art by Christi Belcourt’s, The Wisdom of the Universe, that “the wisdom is in the trees, the flowers, the leaves” from Lorrie Gallant along with Jasmine Wong from Facing History and Ourselves. We were taken through the exhibit by to women, Paula Gonzales-Ossa who identifies as a descendant of the Incas, a Quechua khipuand and Marie Laing who identifies as Mohawk. We learned from Norval Morrisseau’s Man Changing into Thunderbird, an expression of a “heart based language” speaking to spirituality and transformation. We learned from Nyle Miigizi Johnston’s Diiyah Muh’gaanag (Our First Family) of the importance to take time to heal and that this space is a place for storytelling and pausing. We learned from Ruth Cuthand’s piece, Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink, about empty promises and frightening realities of the many Indigenous communities under boil water advisories. We learned from Tim Whiten as we stood around his work, Metamorphosis, a bearskin, covered in a cross, lying on eggshells and though I am not sure of it’s meaning I read it as tradition, colonization, spirituality and fragility that lies in this balance.

`

`

We learned from a dialogue between Wanda Nanibush and Niigaan Sinclair who act more like siblings than former classmates. Niigaan admits to the rivalry he had always felt towards her at Trent, their alma mater, because Wanda was so high achieving and his marks paled in comparison.

We are told of the importance of centering Indigeneity, and not just working to remove the products of colonization such as patriarchy, Christianity and homophobia. Wanda Nanibush explains that moving forward is to always ask ourselves, “Where am I?” and then, “Who was here before me?” She says, “Start where you are standing” and urges the educators to stop telling the story of Canada as a vast empty land and know that before we settled on this land, there were rich, diverse civilizations, complex trade routes, confederacies, laws, languages, and a people, so many people, that despite every effort of the colonizers to commit mass genocide, they are still here.

We are told of the importance of centering Indigeneity, and not just working to remove the products of colonization such as patriarchy, Christianity and homophobia. Wanda Nanibush explains that moving forward is to always ask ourselves, “Where am I?” and then, “Who was here before me?” She says, “Start where you are standing” and urges the educators to stop telling the story of Canada as a vast empty land and know that before we settled on this land, there were rich, diverse civilizations, complex trade routes, confederacies, laws, languages, and a people, so many people, that despite every effort of the colonizers to commit mass genocide, they are still here.

We close the day in circle led by Professor Amos Key Jr. of the University of Toronto. He tells us that he is a member of the Mohawk Nation at Six Nations of the Grand River in Brantford and that he is Ongwehonwe - of the Haudenosaunee peoples. He explains that his people are not a culture but a civilization as he stresses the importance of naming the civilization and the people and not to reinforce a monolithic culture by referring to all First Nations, Métis and Inuit groups under one word: Indigenous. He explains that to do so is an act of erasure--to make invisible--the many diverse, rich, and thriving civilizations not only on Turtle Island but around the world.

I know that this work is all of our work and yet the statement, “Never about us, without us” rings in my ears as I commit myself to paper as a white settler on this land. Each lesson I have learned, each story that I hold in my heart has been shared with me as a little gift. A moment that tells me to listen and witness. A commitment to know that it is only in relationship based on a deep respect, that we can ever move forward into truth with the aspiration of reconciliation. Sometimes it is through friendship, sometimes through art, and sometimes through poetry and prose...Miigwetch to my many teachers on this day: Elder Garry Sault, Professor Amos Key Jr, Marie Laing, Paula Gonzales-Ossa, Lorrie Gallant, Wanda Nanibush and Niigaan Sinclair. I cannot thank you enough and hope that my intention to honour the lessons you have graciously shared and continue to share with me have been shared in a good way.

I know that this work is all of our work and yet the statement, “Never about us, without us” rings in my ears as I commit myself to paper as a white settler on this land. Each lesson I have learned, each story that I hold in my heart has been shared with me as a little gift. A moment that tells me to listen and witness. A commitment to know that it is only in relationship based on a deep respect, that we can ever move forward into truth with the aspiration of reconciliation. Sometimes it is through friendship, sometimes through art, and sometimes through poetry and prose...Miigwetch to my many teachers on this day: Elder Garry Sault, Professor Amos Key Jr, Marie Laing, Paula Gonzales-Ossa, Lorrie Gallant, Wanda Nanibush and Niigaan Sinclair. I cannot thank you enough and hope that my intention to honour the lessons you have graciously shared and continue to share with me have been shared in a good way.

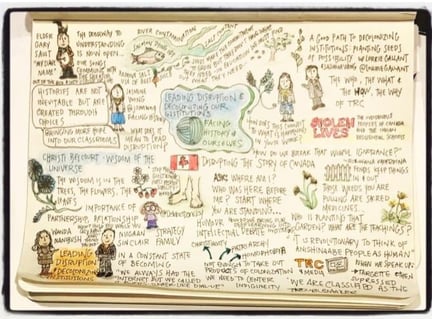

This day was about leading disruption in our schools. Jasmine Wong, from Facing History, reminds us that “histories are not inevitable but are created through deliberate choices.” So we must make the choice to disrupt, to know a truer history, one that speaks to not only the attempts at erasure but also, and more importantly, the richness of the civilizations that have always been here and continue to thrive.

“histories are not inevitable but are created through deliberate choices.” So we must make the choice to disrupt, to know a truer history, one that speaks to not only the attempts at erasure but also, and more importantly, the richness of the civilizations that have always been here and continue to thrive.

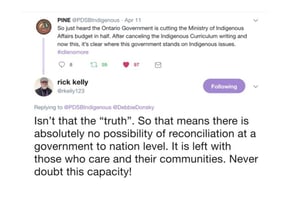

I am asked to write this blog only days after budgets have been cut for Indigenous Affairs and Indigenous Education in particular, and after a history of allies have betrayed Indigenous leaders. The hypocrisy does not escape me.

I can get stuck in the paradox of my position as a white settler in this work or I can do the best I can, seek guidance through relationship and be open to the feedback offered. Complacency is not an option. There is a responsibility to disrupt and decolonize.

Educators across Ontario turn to the Twitterverse to ask for support, find community and renew their commitment to Truth and Reconciliation. We must never doubt our capacity, our commitment and our power to educate. As Senator Murray Sinclair has said that education is the key to walking this journey of reconciliation. I am ready to do that walk. Are you?