This fall, after a suggestion from Jasmine Wong from Facing History and Ourselves, I decided to explore The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative, by Thomas King with my grade 11 English students. I was familiar with the text but it would be the first time I would be using it in my classroom. When I was in school we were rarely encouraged to be critical thinkers and we certainly were not encouraged to seek out the stories that make up our land. My goal was to learn with my students and explore and make connections. I was going to use the idea of the Oral Story as my jumping off point.

The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative, by Thomas King was originally part of the CBC Massey Lectures and so was not originally consumed in written format. So, as a class we read the book out loud or listened to Thomas King tell his stories in order to consume this text orally. We followed along with our books, often stopping to discuss what we heard but we listened to the entire book. The element of oral stories and their value in colonial society came up often during our discussions.

The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative, by Thomas King was originally part of the CBC Massey Lectures and so was not originally consumed in written format. So, as a class we read the book out loud or listened to Thomas King tell his stories in order to consume this text orally. We followed along with our books, often stopping to discuss what we heard but we listened to the entire book. The element of oral stories and their value in colonial society came up often during our discussions.

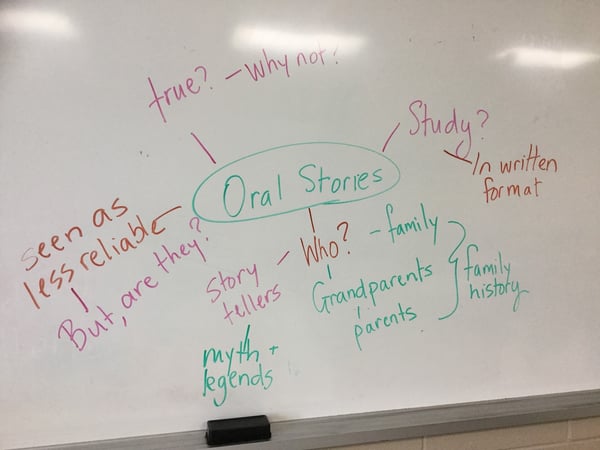

Here are the first of many questions I ask the students before we started:

What is literature? Who decides? Where do our definitions come from? What influences that definition? Why is written text valued more than oral stories in Western Culture/Society?

Is written text better?

Then the students started asking: What is truth (non-fiction) vs fiction? Who’s stories are ‘true’? How do the stories that are part of our history make up who we are?

Photo Credit: Lori Parkinson

Thomas King refers to so many authors, storytellers, academics, and celebrities. Many of these, we were not familiar with and it gave our class the opportunity to explore new sources and ideas. It is important to remember that if we want our literature and ways of understanding the world to reflect and value a diversity of ideas and approaches, if we want to cultivate independent thought, - and we want to pursue reconciliation - we need to expose students to counter-Colonial stories and approaches.

Many students struggled to reconcile their view of Canada as welcoming and multicultural with what they were hearing through Thomas King's writing. Some found it interesting that their families were welcomed and treated differently than Indigenous People who have always been here. One student told me that they were going home and telling their parents what they had learned and discussed in class every day since they had no context or knowledge for what we were talking about. It was interesting to hear from students that our learning was instigating and inspiring them to re-think/unlearn and have these conversations at home.

“It’s yours. Do with it what you will. Cry over it. Get angry. Forget it. But don’t say in the years to come that you would have lived your life differently if only you had heard this story. You’ve heard it now (King 119)."

Project: An Oral Story.

Pick a story you have heard a million times before - a story about you in your childhood, or a family story, how your grandparents met, how you came to this country, your first day of school, anything that you are familiar with and you’ve heard a million times before.

That’s your story.

The students told their stories, thinking about how they communicated these oral stories and what makes a good story. We discussed what made Thomas King a compelling story teller and how that connects to our own stories. As the teacher, and lead learner, at the beginning of class one day as the students quieted, I told them a personal story. It was a story I have told many times before. I used myself as their example and asked the students to provide feedback. Was it compelling? Why or why not? What did I do well? What could I do better? How did I use voice? Narration? Movement? What are the elements of a good story?

The students then were tasked with preparing their own stories. They were placed into small groups of 4-5 students to tell their stories. I circulated to hear parts of all their stories but the students were the ones giving each other feedback. Unfortunately, the first time around there wasn’t enough feedback and as the teacher I felt it would be difficult to mark this project with a few check marks in the little rubric I had given them and one or two comments. After a class discussion the students decided to tell their stories again and provide more feedback.

As a debrief to this project I asked students, "would your story be more valuable or more truthful if it was written down? Has this story ever been written down? Is it part of your family history? Is it recorded in another way? (photo/painting/song)"

Through answering these questions I was hoping my students would recognize that even though written history is held up as the “truth” often, that is not the case. (This is where I also shared the video - The Flood.) One of my students even commented on how written or published text seems to be more valued in western/colonial society but many histories/stories were originally oral or shared in an oral tradition until they were written down.

At the end of the semester, students participated in a discussion panel where they were given the opportunity to discuss what they learned over the semester; their growth both in skill and content.

One of the questions asked was:

“What was the most uncomfortable learning that you have done in this class this semester?” There were many students who referred directly back to Thomas King or to Canada’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples when answering this question. Students were surprised at the history and treatment of Indigenous Peoples but also mentioned that their own ideas and perceptions of First Nations, Metis and Inuit had been challenged by what we learned in class. Several students came to tell me how glad they were that they were a part of this experience and a few students are now involved in school initiatives connected to social justice and reconciliation.

For me the best part was when my students would tell me that they were sharing what they learned with their parents and having discussions at home about our discussions in class. It’s amazing that we are all sharing our learning journey with those around us.

“The truth about stories is that’s all we are (King 2).”

To see all of the resources used during this study click here.