One of the reasons why I love teaching is that I can open students’ eyes to injustices that exist today - injustices like the missing and murdered Indigenous women - and the ways in which they can promote change. The grade 12 Challenge and Change course provides the ideal opportunity to raise these issues, and Facing History’s approach, strategies, and readings give me the tools to authentically engage students.

Designing the Unit

This year I wanted to go more indepth with Indigenous issues in the Global Social Challenge strand of my Challenge and Change course, using my Grade 11 Anthropology, Psychology and Sociology course as a model for how I would design this mini unit. We had already spent time in class discussing inequalities, exploitation, and institutionalized racism, so this mini unit was used to supplement previous knowledge on this topic.

I focused on the following inquiry questions:

- Can we reverse institutionalized racism?

- How can we contribute to reconciliation?

For a full copy of my lesson plans, see here.

I began the first lesson by asking students to write their hopes and fears leading into this topic on sticky notes. Students posted them on the wall where they remained for the next few days as a reminder, and also a source of reflection as we went deeper into a subject that is often not given the voice it needs.

I began the first lesson by asking students to write their hopes and fears leading into this topic on sticky notes. Students posted them on the wall where they remained for the next few days as a reminder, and also a source of reflection as we went deeper into a subject that is often not given the voice it needs.

Raising Awareness for Canada’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Next, we watched a video looking at Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. I felt that starting with a familiar, current and pressing injustice would engage students in exploring the inquiry question: “ To what extent are contemporary injustices faced by Indigenous communities a direct result of the government's historic attempts at assimilation and institutionalized racism?”

After using the give one get one strategy to start our discussions, it became clear that there was only a surface level understanding of the roots of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. And so began my attempts to take my class to the heart of the discrimination.

Creating a Historical Understanding

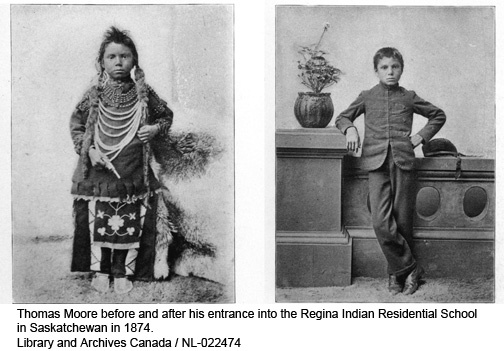

In order to understand the current discrimination against Indigenous Peoples in Canada, we had to go back to the Indian Act and the systematic work of the Canadian government to “Kill the Indian in the Child” through the Indian Residential School System.

My class popcorn read from Stolen Lives former Canadian Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott’s directives. They then went through stations looking at various readings from Stolen Lives in order to understand in detail the crimes the Canadian government, and agents representing the government, committed against the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. Students examined articles discussing first hand experiences at Indian Residential schools; the curriculum of the schools, the impact of language loss, the discipline experienced by many students, and the very real evidence of the physical, emotional and sexual abuse that occurred at these government funded schools.

After discussing with their peers and seeking to understand the impact this racist policy had, students completed an exit ticket following the prompt “Today I am leaving the class grappling with…”. Many students reported struggling to connect the multicultural country they know with the horrific events that occurred, and questioned how so much of the public (including themselves) could have, and still remain, ignorant.

Engaging Students in Ethical Questions

Throughout the next few days we strove to balance historical perspective with the ethical dimension of the Residential Schools. To do this we looked at quotations from perpetrators, victims, bystanders and upstanders.

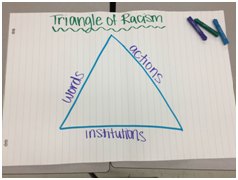

Students really started to understand how multi-dimensional the current inequities experienced by Indigenous Peoples are when I drew the triangle of racism on the board. They were able to see that the racism and discrimination that First Nations, Inuit and Metis people face is comprised of more than just words and actions, but is also experienced and perpetrated through Canadian institutions today.

In order to explore this institutionalized racism we examined the suicide crisis in Attawapiskat, the discussion of cultural appropriation and mascots, and watched CBC’s 8th Fire, It’s Time episode. Through it all we continued to find the strings of institutionalized racism and exploitation that linked to both past and present Canadian governmental policies and colonization.

The Importance of Language

The Importance of Language

I believe the language we use is an important part of the narrative, so on the fourth day we began by reading History In Search of a Name from Stolen Lives. This reading discusses the idea of identifying the Indian Residential Schools as Cultural Genocide. I asked students for their initial reactions by using the text to text, text to self, text to world strategy. Then as a class we read through the reading entitled Genocide, discussing the fact that Canada had only selectively ratified the Genocide Convention.

At the time of ratification, the Canadian government argued that the portions of the Genocide Convention “intended to cover certain historical incidents in Europe that have little essential relevance to Canada” could be omitted. In fact, they even stated that “mass transfers of children to another group are unknown… in Canada.” My students really grappled with this blatant denial by the government of their “Kill the Indian in the Child” policy, and the impact this denial could have on reconciliation. We concluded that by refusing to identify the Indian Residential Schools for what they were, a Cultural Genocide, we are continuing to support institutionalized racism, and deny the experience of the Indigenous peoples of Canada.

We delved even further into this topic as students were assigned either A Canadian Genocide in Search of a Name or Cultural Genocide. Students walked around the room sharing their reactions to both individuals who had the same reading as them, and to those who did not, preparing them to discuss the following questions as a class (adapted from Stolen Lives):

1.How does selective ratification of the convention impact the legal definition of genocide in Canada?

2.What did Lempkin think about the role of cultural destruction in the crime of genocide?

3. How important is intent in understanding genocide?

4. Is the language we use in describing the crime important to understanding and moving forward?

Question four garnered the most discussion. Students made connections to their own lives, feeling that when people try to deny in part or whole a negative experience that happened to them, it makes it harder for both sides to reconcile. They expressed feelings of frustration, anger and confusion over the idea that by denying the past, the oppression is still continuing today. I wanted students to grapple with these feelings, but I didn’t want to end it there. Students need to be aware that reconciliation is possible, and that we all have a part to play. Highlighting the systemic issues at play does not detract from the individual responsibility all of us have to work towards reconciliation.

How do you help your students see large issues but still have them understand the impact they have as individuals to promote change?