When I first found out I was teaching Families in Canada, a grade 12 Family Studies course, I immediately began to consider how I could embed Indigenous perspectives within my course. So often, as history teachers we tend to focus on significant events where Indigenous Peoples experience discrimination. What Facing History and Ourselves' pedagogy reminds me is to acknowledge the resiliency, distinctiveness and contemporary life of the many Indigenous peoples in Canada, their cultures and civilizations in my teaching. This seemed like a perfect opportunity to do both.

I began my planning with a call to my program associate at Facing History. From that conversation, I decided to structure my Family Studies course as an inquiry-based exploration into diverse cultural traditions, beliefs and practices of groups, structured around a life cycle. The course was structured into 4 units: Adolescents and Early Adulthood, Relationships and Marriage, Having and Raising Children, and Late Adulthood and Aging. I wanted to find ways to celebrate various cultures and belief systems within each unit, recognizing that Western ideologies and stereotypical norms do not exemplify all lived experiences, and that all cultures can be recognized and celebrated.

I began with our first unit; Adolescence and Early Adulthood.

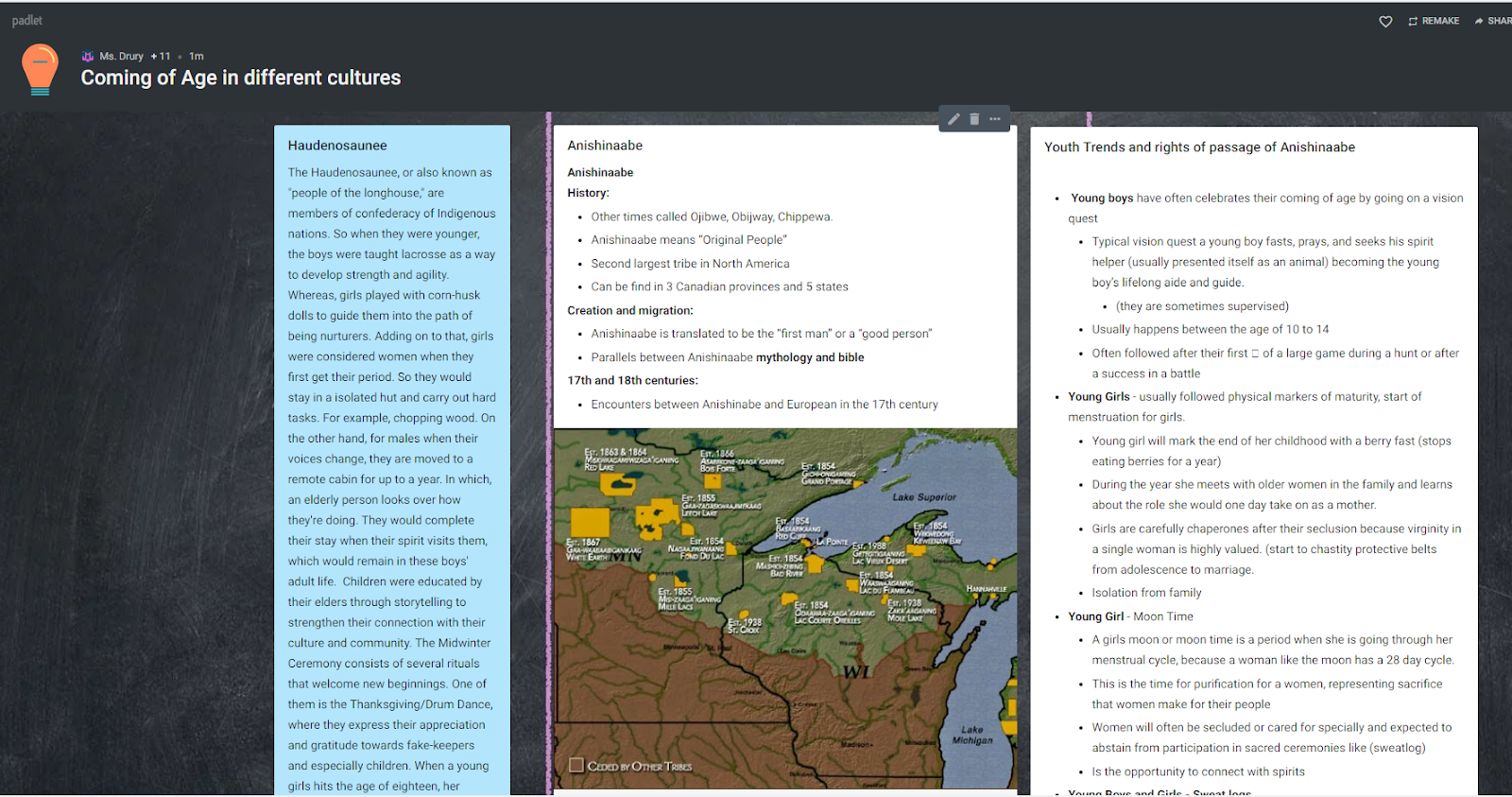

Students began by brainstorming different cultural groups and civilization groups (a term Cayuga scholar, Amos Key Jr. uses to to identify Indigenous groups) within Canada. After some assistance on my part, we developed a list that included (among others) Jewish Canadians, Spanish Canadians, the six nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Anishinaabeg, and Inuit. I divided the class up into groups, and each chose a cultural heritage to research. They used their devices to examine major rites of passage that are marked as individuals pass into adulthood in these cultures and civilizations. Students took notes and then graphically represented their findings on a class padlet, before presenting to the class the various things they uncovered. These images were printed off and displayed in the classroom as we began to create a living life cycle that incorporated many different cultures and perspectives on the aging process. We continued to add to this as the year went on, through our various units.

Padlet used by students to visually represent information

photo credit: Kristen Drury

When we got into our Having and Raising Children unit, I realized that in addition to learning about, and appreciating unique and shared beliefs, practices and experiences across cultures, I would be remiss to leave out an inquiry into the "Sixties Scoop" and the current state of Indigenous children in the foster care and adoption system. The Sixties Scoop refers to the practice of Child Welfare agencies in Canada that fostered the adoption of First Nations and Métis children into families that were all too often non-Indigenous, and often without the knowledge or consent of the Indigenous families involved. At times, these children were even adopted out internationally. This practice has been seen as the continuation of forced assimilation that began with the Residential Schools. As of 2016, “First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth made up 52 percent of foster children younger than 14 in Canada, despite representing just eight per cent of that age group, according to Statistics Canada” (Edwards, 2018). This shows that although officially this practice may have ended, it is in many ways still continuing on today.

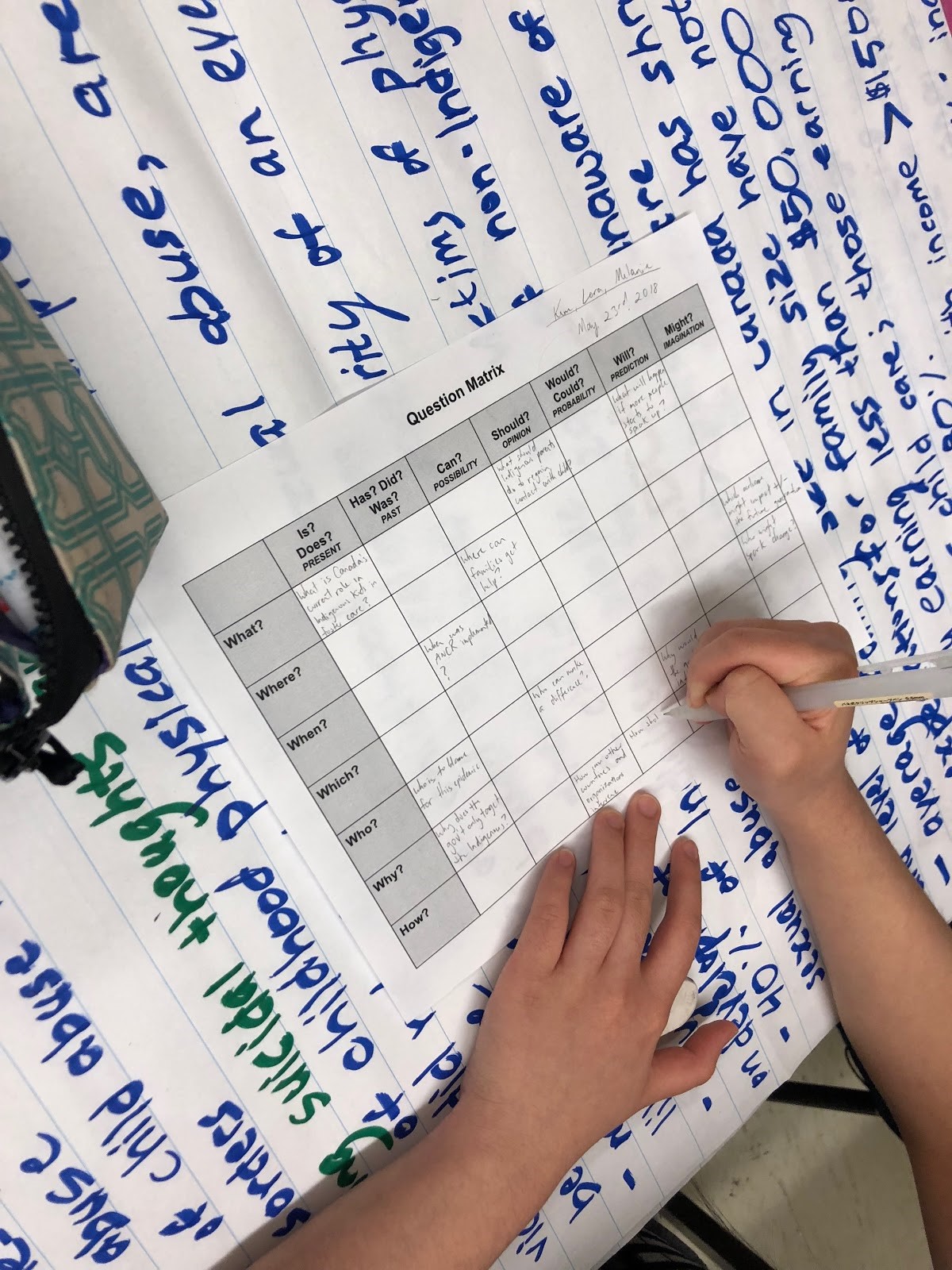

Recently I had read an article and video published by Maclean's that examined this very issue. I began there. In groups students watched the video, read the article, and used a question matrix to generate questions about children in out-of-home care.

Question Matrix photo credit: Kristen Drury

Question Matrix photo credit: Kristen Drury

After examining their questions, I realized that many of my students had questions that reflected a gap in their knowledge of historical contributing factors. The next day, I came in with a chapter from Chelsea Vowel’s Indigenous Writes that examines the Sixties Scoop and how it is still impacting families today. As a class, we read the article, and students went back to their matrix and answered the questions that they were now able to through discussion.

Students began searching social media, local news outlets, their textbooks and the internet in the hopes of finding answers for the questions in front of us. Some of the resources we used were the Sixties Scoop Class Action Lawsuit, Indigenous voices on Twitter such as Jesse Wente and Cindy Blackstock, testimonies found in Facing History and Ourselves' publication, Stolen Lives:The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, as well as stories coming out of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women inquiry.

More often than not, these searches just led to more questions. The question “how could the government continue to do this?” continued to plague students, especially when they considered all the evidence condemning this practice. While we were able to discuss the legacy of assimilation, the fear of the “other,” and the lack of political will for change, there was no definitive answer we were able to reach as a class. Instead, we focused on the role of individuals to advocate for change.

Students expressed feelings of outrage, frustration and disbelief at many of the things that were discussed. In fact, several students felt so passionately about this topic that they took it on as their culminating assignment where they had to find a way to impact change through social action projects. Several wrote petitions to the government, created social media campaigns and designed posters educating people about what is happening in these communities.

Culminating Assignments photo credit: Kristen Drury

Culminating Assignments photo credit: Kristen Drury

How do you embed Indigenous voices in your classes?

What resources do you find most helpful?