In 2015, Dr. Rob Simon, Associate Professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE), and students from his teacher education course partnered with Sarah Evis, a teacher from Delta Senior Alternative School in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), and her grade 8 students, to study Art Spiegelman’s popular intergenerational Holocaust survivor memoir and graphic novel, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Rob has worked extensively with Facing History as a classroom teacher, and has brought Leora and I into his teacher education courses on several occasions. In 2015, Rob received an Early Researcher Award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation in support of a five-year project called Addressing Injustices: Adolescents and Teachers Coauthoring Social Justice Curriculum. Maus is the first of five books he and Sarah invited students to engage with as a part of this larger project.

I caught up with Rob and Sarah to hear about the daring and creative approach they took, and the incredible results that followed.

Jasmine: What was the vision for this project?

Rob: Though students are the most directly impacted by curriculum in classrooms they are the least consulted in its development. This is also true of teachers, who are often positioned as implementers of others’ so-called “best practices” rather than authors of their own.

The Maus project was inspired by what Paolo Freire called “problem-posing education”: inviting teachers and students to be in critical dialogue with each other rather than in more hierarchical relationships. Sarah and I asked ourselves: What would happen if we brought our students together—graduate students from my teacher education courses in the Master of Teaching Program at OISE, and grade 8 students from Sarah’s classes at Delta—to respond collectively to texts that address difficult histories and complex social issues?

The roots of my interest in co-creating curriculum with students are in my years as a classroom teacher, including my work with Facing History. As I’ve shared previously, in the 1990s I helped to start a high school, Life Learning Academy , for adolescents who had experienced significant social and academic struggles. We worked with youth—many of whom had been involved in the juvenile justice system—and residents from a self-help rehabilitation program for former adult offenders and drug addicts called Delancey Street Foundation, to re-imagine what curriculum and school itself could look like.

Fast-forward several years. My son, Elan, was a student in Sarah’s class when I worked on the After Night exhibition. Sarah brought her entire grade 7 class to view our exhibition of paintings by teachers and youth on pages of the Holocaust memoir Night. Her immediate response was: Can we do something like this at Delta?

This was the start of our collaboration. The first book we taught together was Sherman Alexie’s incredible young adult novel, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. We asked teenagers and teacher candidates to co-plan arts projects that Delta students then created. We were blown away and inspired by their ability to work together across differences of age or social location, by their creativity, and how they wrestled with difficult themes in the novel, such as power inequalities, violence, alcoholism, and racial injustice. The projects they produced were stunning. Three years later, Sarah and I continue to challenge ourselves and our students to invent new ways to respond to texts together.

Jasmine: Can you tell me a bit more about your classroom, Sarah?

Sarah: The first thing you would notice about our classroom is the liveliness of the students. The curriculum at Delta is student centered; we teach to the students we have each year, and within a robust but flexible framework that has been in place for many years, we encourage our students to advocate for themselves, and help them to have a lot of agency. In my classes, students have a lot of input into what and how I teach, and with almost all assignments, they have a large array of choices. We have a community circle once a week where we talk about social, personal, and academic issues. The community building work we do in circle supports all the learning we do at our school, and in my classroom.

Our school is just two grades, 7 and 8, one class of each. In their first year at Delta, students are guided more closely; some assignment guidelines are fairly restricted because I want them to learn a particular skill in a particular way. But as they reach the second half of Grade 8, the sky is the limit in terms of what they want to learn about and how they go about doing that. They have a solid base of knowledge to work with at that point so they are able to do in depth, independent, self-directed learning.

Last year one group of students wrote the script for and shot a simulated Delta newscast that involved half the class, and who were mentored by the producer of a local late night news program in Toronto. Another group created and starred in an amazing drag show, and invited a well-known drag artist, Tynomi, to come to Delta to talk about drag, and their own life story. The performance that Tynomi and the Grade 8s did almost blew the roof off, it was so much fun. And it allowed students who had been extremely shy all year, to shine in a way that I could never have imagined.

Jasmine: Can you tell me a bit about the structure of the project?

Rob: Unlike previous collaborations I’ve been involved with as a teacher educator, including the After Night project, our work with Maus was part of the “official curriculum” for both Sarah’s students and teacher candidates in my course.

We began by asking everyone to read Maus over the winter break. In early January, we screened a film about the After Night project at Delta and at OISE to begin a conversation about how the arts can be a way of working through our reactions to the Holocaust.

Teachers and teenagers all came to OISE for our first session together having prepared one question, one connection, and one thing they found surprising about the book. We used these as conversation starters in mixed-groups of teachers and students.

Our first activity in that first session was “big paper.” We used images from Maus and quotes from interviews with Art Spiegelman, and asked groups to have a silent conversation in writing. We then had a gallery walk, inviting everyone to post responses on sticky notes. Over the several years Sarah and I have collaborated we have found this to be a great icebreaker for our students—and a means of surfacing complex ideas about a book.

Sarah: For our second session together, everyone involved in the collaboration met at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) to see CO-MIX, A Retrospective, an exhibition of Art Spiegelman's artwork. We were able to see the original drawings for Maus, and the sometimes subtle changes that Spiegelman made to the individual panels. We looked at the broad spectrum of his work, and many students struggled to understand how the Pulitzer Prize winning author could also be the creator of The Garbage Pail Kids.

Students and teacher candidates filled out question sheets we had prepared to help guide them through the exhibition, and sketched responses to Spiegelman’s work. After our initial viewing of the artwork, we broke into small groups and took time out to discuss what we had seen, and to ask questions; then we went back into the exhibition to look for answers to these questions.

Rob: Our trip to the AGO helped us to understand Spiegelman’s process of creating Maus, and how Maus was connected to his life and work. It was also important to Sarah and I that our students regarded the events of Maus as connected to their lives, not something distant from them.

We asked everyone to write life history narratives about where their families were at the time of the Holocaust. In some cases these involved interviews with family members, who shared stories as well as artifacts. Students and teachers talked about their family histories in groups at the start of our third session together. Using sticky notes, we marked where our families were during the Holocaust on a large map of the world. This helped us to visualize where we were from, to build community, and to see the terrible events Spiegelman describes as more immediate and more relevant.

Jasmine: Maus is an incredibly engaging text, but one that brings up many difficult issues. Why did you choose this particular text? How did Maus align with your larger vision and goals for the class?

Sarah: We chose Maus in part because it coincided with the Art Spiegelman retrospective at the AGO, and a talk that Spiegelman gave in Toronto in conjunction with that exhibition. I had always been nervous to teach about the Holocaust, because of the atrocities that occurred, the age of my students, and the absolute need to get the story and the teaching right in order to honour the people who perished in the camps, the survivors, and their families. Partnering with Rob, and with Facing History, gave me the confidence to do it.

Maus proved to be the perfect vehicle to teach about the Holocaust. Spiegelman uses three devices that allow us to look at the subject matter without completely falling into the abyss: Maus is a graphic novel, it is a story within a story, and the characters are animals instead of people. This gave students different ways into the story and the terrible history it describes, and invited them to express their emotional responses creatively.

Maus fit perfectly with our larger goal, which is to address injustices and to teach and co-author curriculum through a social justice lens. As we are having this discussion, the traditionally anti-Semitic, far-right Front National is poised to make big gains in France, and the lawful segregation of Roma children in parochial schools is happening in Hungary. We are again at a critical juncture in history and we want to give our students as many tools as possible to be able to affect positive change, each in their own way.

Rob: A social justice educator I admire, Linda Christensen, calls texts social blueprints that send messages to readers about what it means to be gay or straight, rich or poor, powerful or not, as well as about race, class, or gender, and therefore persuade us to view the world, history, and each other in distinctive ways. In other words, engaging with literature is always political.

Sarah and I are careful to choose texts that present opportunities for students to call into question commonsense understandings about the world, to see themselves in a different relationship to history and to each other. Maus allowed us to explore the past in ways that encouraged youth and adults in this project to engage with the present, including, as Sarah points out, the many critical issues happening in our current historical moment.

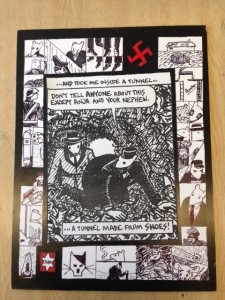

Students’ projects in many cases addressed historical as well as contemporary problems. For example, one group of students and teachers was shocked to discover Holocaust denial websites that promoted anti-Semitic viewpoints. For their project, they built a multifaceted diorama. They took a large box, which they covered in “White Pride” propaganda printed from these websites, and made cutouts through which recreated scenes from the book could be seen that told the true story of what happened in the Holocaust, constructed with paper, velum, paint, collage, and cardboard.

These scenes depict the suffering experienced by Polish Jews: figures of Jews depicted as mice hanging in a public square or huddled in an attic crawl space hiding from Nazi soldiers. In their presentation about their project to the larger group, one of the youth described these holes as representing “the holes in Holocaust deniers’ stories.” Moments like this help us to recognize the empathic connections and critical recognition that youth and teachers make through their work together.

Jasmine: What particular challenges did you face in bringing Maus into the classroom? How did you approach those challenges?

Sarah: Our biggest challenge was threefold: trying to answer the unanswerable question: how can humans treat other humans the way they did during the Holocaust? Leading our students to the point where they were transformed by what they learned, and to simultaneously create a safety net to hold them in while the transformation occurred. This last part was particularly tricky.

Rob: All of the students who read Maus were affected by it. Many of them struggled with their own emotional responses, as well as their encounter with the ineffability and irrationality of the horrors Spiegelman recounts. We knew from the outset that teaching about the Holocaust with young children would be challenging, we were grateful to have the advice and support of Facing History at crucial junctures.

We invited Leora into our classroom at Delta to help us deal with what Sarah called “the unanswerable questions”: How could this happen? What would allow human beings to treat others so inhumanely? Where were ethics, morals, government, or god, in the midst of this horrifying history? How can we make sense of this, or even live with what we have learned about the Holocaust?

One of the common practices in Sarah’s classroom as she mentioned previously is community circle. This is a space for students to address all manner of issues. We sat in a big circle together, and Leora helped to mediate a conversation with students in which they were given space to ask any question, to share their emotional responses, to listen quietly, or process their responses through writing. Leora was incredibly helpful in this, listening back to students’ questions, providing some detailed responses, based on her extensive experience as a Holocaust educator, but also echoing students’ uncertainty and struggle.

Historian Dominick LaCapra has described the Holocaust as an event that defies comprehension. This makes the Holocaust an important but difficult site of inquiry. Instead of arriving at definite understandings, studying the Holocaust requires working through our emotional and intellectual responses. This is an ongoing process.

Sarah: Our second challenge, leading students toward some form of transformation, was more challenging and more apparent in some students than others, but they all felt it. This transformation was obvious in a student who discovered through the family history project that he had lost relatives in Auschwitz, but it was there, too, in students who learned that their families had hidden people from the Nazis.

The most remarkable transformation came about as the result of watching a very short black and white film clip of the liberation of Auschwitz. We had, I think, deliberately stayed away from showing the students footage of the camps, but this clip was part of an excellent resource package one of Rob's grad students, Ty Walkland, put together for us.

One of the Delta students had been working on a painting with her partner, about the camps, including an image of the piles of shoes left behind by the prisoners, for her culminating response to the novel. This was towards the end of our work together, and we had learned so much at this point—about the author, the war, our own families' involvement—but this one 15 second clip impacted this student in a way that none of our previous learning had. Something about the movement of the people as they walked out of the camp acted as a portal and transported her right to the gates of Auschwitz.

The next day, as she was feverishly altering her painting to better represent her new understanding of the human suffering that had occurred, she told me that she had had a breakdown the night before, that it finally hit her that all of what we had been reading about was real. The impact on her was enormous. As teachers, this is the kind of transformational learning we work towards and hope for, but watching it actually happen, and at such an incredible depth, was also heartbreaking.

Jasmine: Asking students to co-design curriculum like this is really unusual. What was the most exciting part of this project?

Sarah: The most exciting part of all the work Rob and I do with our students is to sit back at some point and watch in wonder as they present their learning to us, in such creative ways, and in such great variety. The Delta students created everything from a recreation of the Marshall Plan to the diorama Rob described which demonstrated the dissonance between what we had learned during this project, and the lies they found online written by Holocaust deniers. When we see presentations like these, we are affirmed in our belief that some of the very best work our students do is when they are given free reign—within the framework we have co-created.

Rob: There are so many moments in our work together that I find gratifying, surprising, and inspiring. I think our work as teachers is to provide our students whatever support they need to be brilliant. One of the OISE teachers said in response to the projects Delta students created, “This goes way beyond my wildest expectations.” I feel like Sarah and I continue to learn more from our students than they learn from us.

Jasmine: Walk our readers through how you prepared students to be ready to co-create their own culminating tasks. What supports and guidance did you give them?

Sarah: A lot of the preparation was part of their day-to-day learning at Delta. A lot of our learning is self directed, and our students, as I mentioned earlier, have a tremendous amount of free choice within the projects they are assigned, so they already had quite a bit of experience in co-creating projects, although we didn't call it that. Added to this was the depth of learning we did about Art Spiegelman, his work, graphic novels as a medium, and of course, the Holocaust.

During our collaboration, Rob's MT students took the lead in small group discussions helping the Delta students to explore the particular themes and issues they were interested in, and to flesh out their ideas. The graduate students working with us guided the students to helpful resources, and Ty oversaw the digital scrapbook project.

Perhaps the biggest support we gave them was emotional support. Rob and I needed to be grounded and emotionally present at all times when we were working with the students on this project. Or most of the time. Plus we had support from Leora for ourselves and for the students.

Rob: We learned in previous years that it was important to give students the space and time they needed to process their responses to texts like Maus. Too often in classrooms we feel compelled by shortages of time or resources, outside pressures or expectations. We march students through the curriculum rather than allow our experiences with texts to breathe.

There were many aspects of the project that developed in process. For example, Delta students were left with unanswered questions. We decided to write Art Spiegelman to share our gratitude, our admiration, as well as our questions with him.

Jasmine: What were the big successes for this class project for yourselves? What about for students?

Sarah: There were so many! Watching the deep, transformational learning taking place was amazing, and the biggest success for me. And doing a good job of tackling such a difficult subject matter, with middle school and university aged students together, that was very exciting.

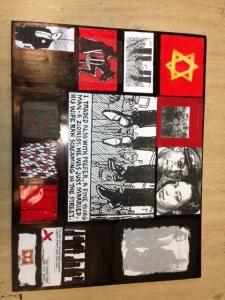

For their final response to Maus, we invited the Delta students to create a group conceptual art project. The inspiration for this project was a series of paintings done by Pierre Alechinsky in response to the atrocities of the Second World War. Alechinsky’s paintings include many separate panels, which are reminiscent of the panels in Maus, so they were a perfect inspiration for my students' own art.

Students were each given a foam core board (14" x 20"), access to imagery from historical texts, and various art supplies. The central panel of each of these artworks is taken directly from Maus; students were directed to choose the one image or series of images from Maus that they connected with the most as a jumping off point. Students used multiple media to respond to panels from Maus—they made collages of images and painted their own—some using primarily black, white, and red, others choosing to use a full palette of colours.

This was a meditative process that resulted in some of the best work I have seen from students. The collage aspect allowed all students, including those not confident in their drawing skills, to create incredibly powerful and visually exciting artwork, as you can see from the images we have included with this article.

Jasmine: What are the next steps for this project?

Rob: We are in the process of putting together an exhibition of student artwork from the Maus project, which we hope to display locally. Sarah and I are also co-authoring an article with 15 students about this process, along with several OISE teachers. The article will include a “virtual gallery” of the panels Sarah described, alongside students’ writing about the choices they made as artists, what the work means to them, and what they took from this experience. We met with students last week to begin the writing, and were reminded of their thoughtfulness, and their unique commitment to this project. How rare is it for a group of students to remain connected to a school project many months after graduation?

As a teacher educator, I want to create opportunities for my students and I to learn alongside adolescents, rather than talk abstractly about curriculum or approaches to teaching a book like Maus. As a researcher, I want to find new ways to invite students and teachers into the research process. I continue to be amazed by the results.

Sarah and I plan to work with five different texts over the next five years, and our hope is that we will be able to collect this work in an edited book that will include curriculum, artwork, and reflections by teachers and youth who collaborated with us. In the meantime, we are beginning to work with our next text, a novel called Beautiful Music for Ugly Children, that is told from the perspective of a transgender teen. We had workshops for OISE teachers and Delta students this month in preparation for our work together with Beautiful Music in January, which will include writing curriculum for the book, as well as a digital storytelling project. We can’t wait to see what our students come up with.