In this post, Social Studies teacher Lindsay Hutchison and Math, Science and Careers teacher Mariam Hazhir reflect on their teaching following the murder of George Floyd last June and share how they seek to practice antiracist educator mindsets, foster reflective conversations about racial inequity as allies, encourage critical consciousness and outline five principles that teachers of all disciplines can practice.

As many teachers across Canada have made the shift to online or hybrid learning and shortened time frames, we think about what it might mean to prioritize essential learning; for us - and for many teachers - making sense of the injustices in our world is essential learning and it can - and should - include all educators. Whether you teach Social Studies, Math or Science, Careers or Physical Education, our students need to know we see them and support them; we can also help them to connect subject disciplines to each other, and to our experiences and applications of these disciplines in the real world.

Here are 5 guiding principles that we use:

- Structuring classrooms to make space for anti-racism work

- Create a brave space for conversations about inequity and (racial and other) injustice

- Work with colleagues to build a school culture supports racialized students

- Give students space to process injustices in the world

- Continue the conversations

1. Structuring classrooms to make space for anti-racism work

Mariam: If we want to promote anti-racist pedagogy, we must start with ourselves and for me this begins with the structure of my classroom and my day-to-day interactions and relationships with students.

- If we are in a face-to-face classroom setting I make sure to structure my classroom so that I am not standing at the front. Instead, we sit in a circle so that we are all on the same level.

- I try to emphasize that experiential knowledge is just as important and valid as knowledge that we derive from texts. Therefore, I try to focus on First Peoples Principles of Learning and provide spaces for students to speak on their experiential knowledge.

- I tell students in my classrooms that I do not know everything, that they should feel comfortable addressing me if they feel that I am being unfair, unjust or racist. Some teachers may be worried that students will take advantage of this however, I can assure you this has not been my experience at all. What this does is help students realize that they have the power to hold people in positions of authority accountable for justice and human rights.

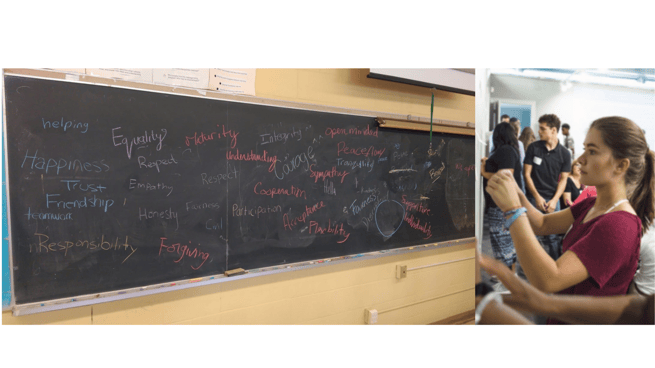

2. Create a brave space for conversations about inequity and injustice

Lindsay: Conversations about racial injustices are not easy conversations to have but they are necessary.

At the beginning of my Genocide Studies course I use “Untitled Poem” by Beth Strano* to introduce students to the difference between a ‘safe space’ and a ‘brave space.’ As part of this conversation I acknowledge my white privilege. I think modeling this critical reflection is essential if we want our students to do the same thing. Consequently, I share with the students a little about my upbringing in predominantly white spaces and what I’m doing to educate myself about racism and the structures in our society that perpetuate it. I admit to them that I have made mistakes. I encourage them to have difficult conversations – with me, with themselves, and with others. Then we co-create a classroom contract to guide our work and learning together. We often refer back to this contract prior to engaging in difficult conversations.

*Note from Facing History: This blog post was updated in July 2021 to correctly reference a poem by Beth Strano, "Untitled," posted to Facebook June 25, 2021. We originally posted a version of this poem attributed to Mickey ScottBey Jones. After learning that Jones' version was plagiarized, we have replaced it with the original poem by Beth Strano. Please use Strano's version going forward.

Other protocols I use in my classroom to foster a brave space to talk about inequity and injustice include:

Other protocols I use in my classroom to foster a brave space to talk about inequity and injustice include:

- ‘Tap Out’- I allow students to temporarily ‘tap out’ if they need a break during emotionally charged content. How they choose to ‘tap out’ is up to them. I also emphasize that we will all experience these difficult moments over the course of our time together but that we won’t all experience the same ones at the same time and there will be no judgement. I follow up with them privately to help them or guide them to someone who can help them.

- Journals- Students respond to either a specific question or record their thinking on a topic or experience in general. Some students’ journals take on a graphic form, others write, and others employ a mix. When I collect the journals I respond first by thanking them for sharing and for their vulnerability. From there, I engage in a written dialogue with them.

- Exit Cards- I use anonymous exit cards to allow students to respond to their learning and/or ask questions; at times I couple the 3-2-1 and S-I-T strategies with exit cards to get more specific feedback. If any trends or questions arise from the exit cards I make sure to immediately address them next class. I find this strategy particularly useful for them to share their reflections, questions and emotional responses.

For example, after engaging in a lesson that involved watching clips from A Class Divided (where educator Jane Elliott speaks the “n” word in addressing racial injustice) some of my students wrote in their exit cards about feeling that I had not done enough prior to viewing to adequately address the dehumanizing language in the clips. After seeing these comments, I realized the trauma that I caused and the need to do some more learning. I consulted “Addressing Dehumanizing Language from History” and have continuously engaged with other readings. The next morning I apologized to the students along with personal check-ins and we talked about my learning, reinforced the importance of acknowledging and voicing when a harm has been spoken or done, and what I would be doing differently in the future.

I think it’s imperative that we begin to invite students to hold teachers and students equally accountable to the shared norms of the class. Not only does this allow us to build shared norms throughout our time together, it also allows us to honour the humanity of each member of our class.

Photo courtesy of flickr.com

Photo courtesy of flickr.com

3. Work with colleagues to encourage a school culture that supports racialized students

Mariam: School staff is like a family where students look up to us and want to see that our values align. In order to tackle this mission to centralize anti-racism work at our school, Lindsay and I worked together to create an email where we reminded staff to be particularly mindful that many students, and Black students in particular, may be experiencing immense trauma right now. I asked staff to join Lindsay and I to make posts to their classes (in June) about Black Lives Matter and George Floyd’s murder. Allyship must be explicit so that students feel empowered and safe in your classroom but also so that you are held accountable to make sure you are doing the work to centralize anti-racist pedagogy.

Here are a few things we did we do to demonstrate our solidarity with students of colour long term.

- Acknowledge the situation even if it made us feel uncomfortable. We all have different starting points and that is okay. I always tell my students this - it is not about saying it right the first time but rather starting the process.

- We show up to events that are in solidarity with Black, Brown, and Indigenous, students. It is especially important to show up (in spaces where allyship is welcomed) for students whose identities have historically been unacknowledged or relegated to particular days or months of celebration. Students are always watching. They notice who is there and who isn’t.

- We step in when we witness a colleague saying something problematic to another colleague. This includes both micro-aggressions and outright dehumanizing comments. The times I have voiced my concerns, I am quite nervous and am waiting for other colleagues to step in. In many instances I am left alone and only receive messages afterwards saying “I am so proud of you for being brave”. The intentions behind such messages are supportive , however it can make the person who is standing up feel like the responsibility is now solely on them.

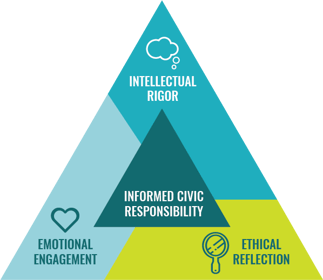

Facing History's Pedagogical Triangle

Facing History's Pedagogical Triangle

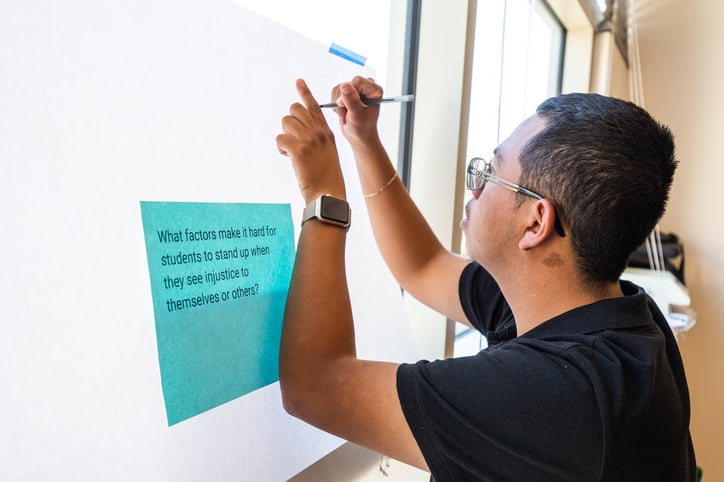

4. Give students space to process injustices in the world

Lindsay: Like Mariam, I also wrote a message to my students expressing my emotions about the murder of George Floyd and encouraged them to message me if they needed to talk. I scheduled a virtual class meeting solely devoted to addressing the murder and the resulting protests. Because language matters, I framed our meeting as a “check in” as opposed to a lesson. I began our meeting by sharing my emotions about what was happening.

- Wraparound Strategy: I then used this teaching strategy by asking students to share an emotion or question related to what they were reading, seeing and hearing. As each student shared, I wrote down all the questions and addressed what I could. For the questions I couldn’t answer, I told the students I would find the answers and return to them in a future meeting.

- Polling and Discussions: After the wraparound I invited students to respond to an embedded anonymous digital poll asking “who has watched the video of the murder of George Floyd?” A majority had. I used this to discuss what it meant to witness viral moments that document the deaths of Black people and it led to a discussion about dehumanization. Next, students responded to another poll about where they get their information from, which led into a discussion on the pros and cons of each media source. We closed the meeting with a promise to keep learning.

5. Continue the conversations

Lindsay: I didn’t want our initial check in meeting to be the end of the conversation and so we continued these ‘check ins’ each week. Although these subsequent conversations were less structured than the first, we always began with a wraparound as an emotional check in. After that we talked about what we read and watched, we asked questions, and shared resources – many of which I posted on our main discussion board so that students could return to them. We also discussed ways to be an ally. I continued to remind the students of my availability if they wanted to message me privately to ask questions. A surprising number continued to do so.

Mariam: Continuing the conversation is imperative. I also started a discussion thread with my senior students by posting Jessie William’s BET speech from 2016. This sparked a great discussion around Black Lives Matter, George Floyd and other issues of racism. It’s important to note that acknowledging that you are an ally for Black Lives Matter does not stop racism. It should be demonstrated in your everyday work as an educator.

Each of our choices can impact society and as we teach students to speak up when injustice takes place in the classroom, we are also modeling and allowing them to practice behaviours that will help them to be the change they want to see. How are you creating space in your classroom to invite these important and meaningful conversations?

Additional resources:

- To understand more about the US context and the murder of George Floyd see Facing History resource ‘Reflecting On George Floyd’s Death And Police Violence Towards Black Americans’.

- To hear more from scholars and anti-racism advocates and educators head to our on-demand webinars to find a range of speakers and voices.

- To learn more about building critical consciousness in a Canadian context watch Dr. Nicole West-Burns’ TEDtalk ‘Building Critical Consciousness for Educational Equity’.

- You can read more about what we're reading and how we think about teaching for equity and justice in this blog post.