As an organization, our mission is to use lessons of history to challenge teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate. In this blog post, we share our learning (thus far) about how we can work to be anti-racist educators in hopes that this approach, the ideas, and the resources we’ve found helpful in our learning will be helpful to you, your colleagues and the students you teach.

At Facing History and Ourselves, we believe that the process of engaging in meaningful dialogue on anti-racism - and personal and institutional change - begins with self-reflection and a connection to why this work matters to us personally. We then seek social, psychological and historical understanding that fosters critical consciousness about contemporary realities. For meaningful change, this reflection and learning must then translate to thoughtful partnership, action, and a willingness to evaluate and challenge existing power dynamics in classrooms, schools and school systems. This approach for engaging as co-conspirators (a term used by Bettina Love for allies who are willing to be uncomfortable, to sacrifice and to collaborate for equity) in anti-racism work has its foundation in our “scope and sequence” or “the Facing History Journey.”

1. Beginning with Identity

Our approach to becoming anti-racist educators starts with thinking about our identities. In doing so, we:

- Consider the relationships, values and hopes that are central to who we are, and why we engage in teaching for justice and equity. Theodore Fontaine, Kim Wheatley and Lorrie Gallant teach us the centrality of seeing ourselves and the choices we make in relationship to all living things, to the past, present and future generations.

- Surface awareness for the intersectional, complex reality of our identity.

- Surface the role that social forces play in shaping our identity and the choices available to us, and ultimately the choices we make because of our identity (or the perception of our identity).

- Consider and reflect on our positionality (our social location, worldview and how it impacts our interactions where power differentials are present) as educators, actors and co-conspirators.

- Become aware of and begin to articulate our personal and emotional triggers. Diane Goodman teaches the importance of this awareness for self care in this work.

- Begin to acknowledge the biases and blind spots we will have.

What Might This Look Like in an Organization?

Our Canadian Facing History team is a small group of individuals with diverse ethnicities, ancestral origins, religions, languages, class backgrounds, ages, and life experiences who share in the mission of Facing History and Ourselves. As an office, we have created an intentional space and dedicated time to discuss our identities and experiences and to assess our biases.

As an office we have reflected upon instances of our own complicity and moments when our implicit and explicit biases led to harm and sought to change our misperceptions and actions. Steve Becton, Chief Officer of Equity and Inclusion at Facing History and Ourselves, calls this the process of ‘falling forward’ when we make mistakes. In reflecting on our mistakes, we have sought to be intentional about why, when, where, and with whom we are processing through our actions. We seek to avoid placing expectations on those who are navigating their own experiences with racism to explain, unpack, or to forgive our missteps and mistakes.

Our learning and awareness of our own identities also impacts and necessarily informs how we approach our work as educators who often teach histories that are not ‘our own’:

- As individuals and as an organization, we seek to be proximal, in relationship with, and guided by those who have lived experiences that we do not share, particularly where we work to understand and (in the words of Beth Strano) “amplify voices that seek to be heard elsewhere”*.

- We move forward with humility, courage and relentlessness.

- We use the platform and resources we have to create spaces for others, we learn and model ways to build bridges across differences, and we co-conspire to create change.

- We make space to reflect on, and anchor ourselves on our hopes for engaging ourselves and others in learning, and we acknowledge our fears, and listen with care for the fears of others (particularly when others have been impacted directly by injustices).

*Note from Facing History: This blog post was updated in July 2021 to correctly reference a poem by Beth Strano, "Untitled," posted to Facebook June 25, 2021. We originally posted a version of this poem attributed to Mickey ScottBey Jones. After learning that Jones' version was plagiarized, we have replaced it with the original poem by Beth Strano. Please use Strano's version going forward.

2. Understanding ‘We and They’

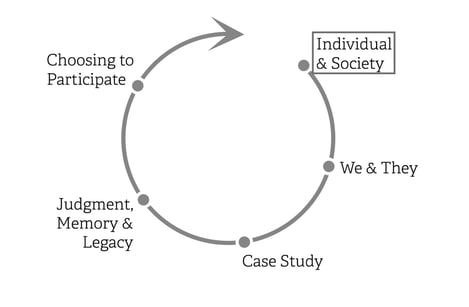

.jpg?width=481&name=S%26S_graphic_updated2019%20(1).jpg)

It is important to recognize how group divisions are part of who we are as a human species, how they have been created historically, and how they impact us today. By recognizing that it is in each of us, and how it operates, we can begin to see and undo what Beverly Daniel Tatum calls ‘the smog’ of racism. In this process, we ask:

- What forces divide us into the we/they?

- What beliefs and ideologies dehumanize some groups and privilege other groups?

- What stereotypes and biases do we hold about some groups, and how have we arrived at these?

- How can we be purposeful about individualizing behaviours, rather than seeing behaviours as part of groups?

- What are some of the costs that I, those I teach, or my communities incur by leaving racism and white supremacy unaddressed?

When we start engaging in a topic outside of our identity, we also ask ourselves:

- How will my positionality help inform and guide the work that I do?

- What is my approach? Who or what voices do I seek out to make sure that I humanize individuals and see diversity within groups?

- Who or what voices do I seek to avoid learning and teaching single stories (especially stories of trauma or deficit)?

- Whose voices are missing from my existing teaching practices? Why?

- Who should I be engaging in partnership with from the beginning when I plan and teach these topics?

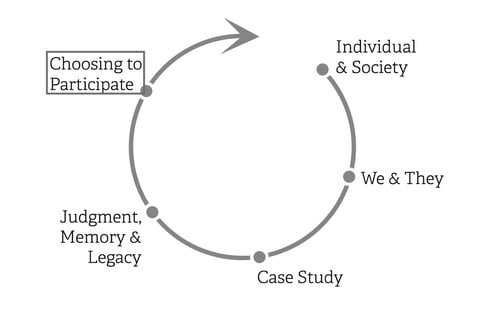

3. Case Study and Judgement, Memory & Legacy: Understanding Contemporary Issues Through a Deep Understanding of History

.jpg?width=472&name=S%26S_graphic_updated2019-1%20(1).jpg)

As an organization, we know that in order to fully understand today’s inequities and injustices, we must look to the past to understand the root causes for, and institutionalization (in law, policy and practice) of injustices and inequalities over time. Knowing history helps us to interpret present realities with clarity, and see how to undo root causes for injustices and inequalities or to mitigate its impacts on those we teach. Moreover, knowing history that centres the scholarship and voices of individuals who have experienced history are essential for ensuring that our learning is grounded in the humanity and agency of individuals within a group.

As a team we have been reading, and listening to the resources that are listed in this blog (click here). This collection includes historic and contemporary texts and features scholar voices from several fields as well as first-person accounts.

4. Choosing to Participate

While the first step of the Facing History Scope and Sequence investigates the ways that society influences the individual, this last step in the cycle explores the many ways in which individuals can influence the society in which they live.

For the last 12 years, we have been learning as a non-Indigenous organization about what it means to be true co-conspirators with our Indigenous partners (the scholars, educators, survivors, and students we are so lucky to work with). We are actively engaged in this same process of learning as we think about the role we can play in partnership with Black scholars, educators, students and leaders. We recognize that the actions that we take as an organization must happen while we continue to learn, and listen.

Our Commitment to Choosing to Participate:

- Using our individual and organizational voices, skills and resources to highlight and give power to those whose scholarship and teachings need to be learned and heard.

- Engaging with educators who we have relationships with to better inform and guide the work that we do.

- We’ve been taught by our partners, Jennifer Henderson and Michelle Evans, the idea of extractive vs. reciprocal content development.* As we develop new resources and materials, we are committed to working in non-extractive practices. This means that we will amplify BIPOC voices, work with BIPOC writers for content development and co-create resources through building reciprocal relationships.

- Through our resources, we are ensuring that students are given opportunities to hear from and see diverse sources of knowledge by quoting directly from BIPOC scholars, authors, individuals and including pictures of those individuals.

- Highlighting stories of Black and Indigenous strength and resiliency by giving space and opportunities for diverse speakers to share about their identities, experiences and knowledge.

*Michelle Evans and Jennifer Henderson would like to recognize those who continue to teach them about reciprocity and non-extractive practice: Chief Kelly LaRocca, Dr. Karyn Recollet, Elsie Millette, Isaac Day, Nancy Rowe and Thelma Mac Donnell.

The Facing History scope and sequence ends with an arrow connecting the final stage ‘Choosing to Participate’ to the first section ‘Individual & Society’. This visual is reflective of our commitment to anti-racism work. We understand that this work is a continuous process that must be approached as a lifelong commitment. We are dedicated to revisiting, refining and continuously reflecting on our approach so that we can do this work in the best way possible.