“We are all treaty people” is a phrase often used in Ontario to remind us of the agreements that have helped form Canada, but when we look nationally this is not true: Much of British Columbia is without treaty, and in the Territories there are other agreements like the creation of Nunavut, that serve to demonstrate different ways of being in good relations. It is important that we understand the role and significance of treaties - and consider the importance and implications of non-treatied lands and territorial agreements - our responsibility to these important agreements and the ramifications of not having them or not honouring them.

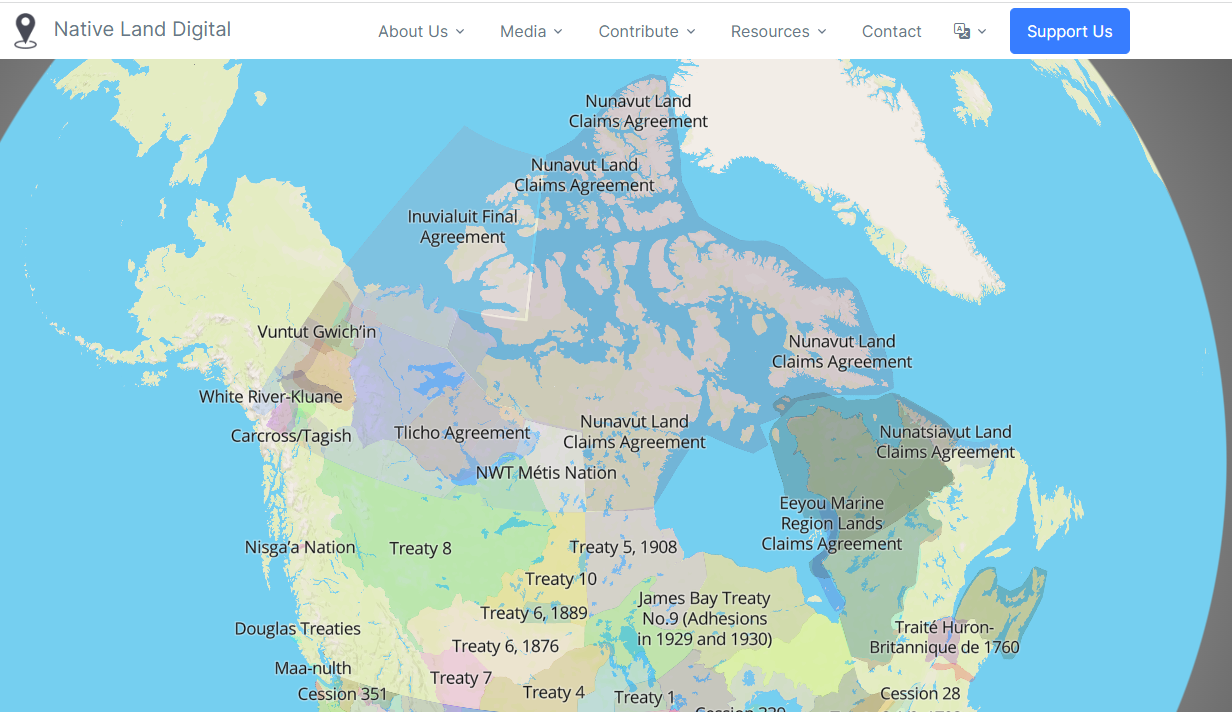

This screen capture is taken from the Native-land.ca site as of the publication of this blog, mapping the treaty areas, un-treatied areas, and lands covered by agreements across Canada.

Across Canada, treaty days offer opportunities for recognition, maybe celebration, and certainly teaching about treaties to improve our understanding of treaties between Canada and First Nations. In Ontario, Treaties Recognition Week takes place during the week of November 5-11 2023. In preparation for this week, we have worked with educator Andrew McConnell (Anishinaabe/English, member of Nipissing First Nation), and educator, Maria Savvides (Secondary Teacher at Humberside Collegiate Institute, TDSB), to publish a list of resources and teaching ideas to support you with your learning and planning.

These lessons are ordered to support the introduction of treaty topics to students.

- They start with an examination of what treaties do and why they have been made.

- From there they move to looking at treaty and legal traditions that exist in and between First Nations.

- After that there is a look at what happens when the treaties are not honoured and ramifications for both sides.

- Finally there is a look at the newest agreements between Canada and Indigenous people.

These lesson ideas lay out the approach, values and legal imperatives written into treaties, the consequences of breaking these treaties and the possibilities for renewed relationships and treaties honoured.

The lessons can be timed for 30 to 45 minutes each and serve as an opportunity for students to explore ideas, documents and move into discussion. They can be tailored for students from grades 7-12 and support lessons related to history, civics, law, geography and English.

Why are we writing this series?

It is treaty recognition week in Ontario. Whether there are treaties in your area or not, they remain a significant topic of importance for Canadians and Indigenous People. Understanding these agreements and their historical context is crucial to improving future relations between the many different people who live here and our various governments. This will continue to be true as many First Nations and Métis people continue to work out new arrangements with all levels of government in an age of renewal and hopefully reconciliation.

Treaties reflect the diverse relationships that exist across Canada, from coast to coast to coast. They were crafted to address region-specific issues at different times and continue to set out the relationships that we see today. They are enshrined in the Canadian constitution and are based on the Royal Proclamation of 1776. As we continue with our blog posts, it is important to remember the significance of living in harmony with others, and acknowledging that all Canadians, regardless of when they and their families arrived, are in a relationship with Indigenous peoples.

Day 1- Building Foundations: The Agreements We Make

It's essential to start by discussing what a promise is with students. A promise is, at its most basic, an agreement between people that establishes a relationship based on mutual respect, whether it's agreeing to meet somewhere at a specific time, to remain friends into the future, or to agree to pay for the use of something.

The complexity of a promise and the number of people involved though will dictate the rules that are involved in order to remedy any disagreement after the fact. For instance, a promise to meet for dinner at a specific time on a particular day is a simple promise, while a promise regarding territory sharing comes with more intricate responsibilities.

In treaty making, this has included expectations of reciprocity, equal access, or monetary payments, depending on the nature of the agreement. Recognizing these differences in promises is vital in understanding treaties.

Activity 1

Pair the questions below with a reflective dialogue strategy like Rapid Writing then invite students to share with a partner using one of the following kinesthetic dialogue strategies, pick a number (modifying with questions) or 4 corners dialogue, by assigning a question to each corner and inviting students to choose a corner.

- What is a promise? What does a promise mean to you?

- How and why do you honour your promises?

- What does working and being in a good relationship require?

- What does/should it look and feel like to nurture good relationships?

- What are verbal promises?

- What are written promises?

After students discuss their ideas about personal promises and commitments to maintain good relationships, explore this final question together:

- What expectations would you have for others with whom you promise to share space, or to share land?

Activity 2

Introduce students to an example of a legal agreement for land sharing, made in a social media era. Ask students to read the CBC article below

-Oct-30-2023-05-29-29-8742-PM.png?width=512&height=296&name=unnamed%20(1)-Oct-30-2023-05-29-29-8742-PM.png)

"People don't [always] understand the consequences of digital communications, but they're the same as any other form of communication. You're bound by what you write. Even if it's an emoji, it's a mark," Lee said. (CBC)

Discussion Questions

- What is the significance of the court’s decision?

- What are the implications of this settlement on how Canadian courts view promises and agreements (between individuals, or organizations)?

- What might the implications be for a nation where its justice system does not uphold agreements?

- How do the farmers' choices in this article, and the court's decisions connect or extend your thinking about the responsibilities held in agreements to share space.

Day 2- Indigenous Communities and Treaty Making

Treaty making didn't arrive with Europeans. It already existed in the lands now known as Canada. There were many agreements between the various First Nations. Agreements made among many Eastern nations were recorded in Waampum belts that were accompanied by stories, while agreements among many West Coast First Nations were accompanied by feasting, carvings, stories, songs or dances. These explained why the treaty was made and how it would be administered. Many of the relationships still exist today, from the Three Fires Waampum that describes the relationship between the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatami, the the Dish With One Spoon Waampum that explains the relationship between the peoples of the Great Lakes basin.

That's why many - although not all* - First Nations were prepared from the beginning to enter into relationships with European powers when they arrived. Evidence of this can be seen in the early treaties such as the 1850 agreement made on Victoria Island, Peace and Friendship treaties of the Maritimes, and later settlements created to open lands to resource extraction and maintain relationships with the First Nations of the areas, like Treaty 8 and the Robinson Huron treaties. These first treaties have since been subject to many court cases, in response instances where treaty conditions have not met, but it should not be assumed this occurred due to a lack of understanding on the part of First Nations. For example, there is evidence that some BC First Nations wanted formal treaties with the government of Canada, such as the Nisga'a who reached out in 1887 looking for a formal arrangement which was rebuffed until the treaty of 2000.

Professor Hamar Foster adds that in addition to the challenges of unmet treaty promises, "of course, how governments and First Nations understood treaties generally was clearly different, one side regarding the heart of the agreements as land surrenders, the other believing that the purpose was to share the land, and regarding assurances that hunting and fishing rights would be respected as meaning that things would continue much as they were."

In this lesson students will look at the treaty relationships that First Nations have made and maintained, which make up part of Indigenous law in the lands now known as Canada and the earliest recognition of Indigenous land rights, the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

*When the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia advanced the legal case for treaties, they were opposed by representatives of some of the Interior Tribes before a parliamentary hearing in 1927. Even today, some FN’s – those associated with the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, for example – have not entered the treaty process that began here in the early 1990s.

Activity 1: Introducing the values, beliefs and underlying principles to Indigenous law and treaties

Legal scholar Aaron Mills writes in the McGill Law Journal, “Law is a dynamic force. Western written law contains Western values, beliefs and precepts that dictate thinking, behaviour and approach to justice.” In the same way, he and other Indigenous legal scholars - Sákéj (James Youngblood Henderson), Patricia Monture and Leanne Simpson - write that Indigenous law must similarly be understood through an understanding of the values, beliefs and principles (these, combined with language and ways of knowing are referred to as lifeworlds) held by each Nation.

In this activity, we read Peter Ginnish’s story to introduce some of the values, beliefs and underlying Mi'kma'ki principles and how the Mi’kma’ki demonstrated these principles with newcomers to Burnt Church, New Brunswick.

Please Note: The use of the term Indian, is a highly problematic and harmful term used to refer to Canada’s Indigenous peoples, and one that is not promoted or permitted to be used. It is only within the context of Canadian Law and Indigenous laws, and this unit, that this term may be used.

-4.png?width=590&height=562&name=unnamed%20(2)-4.png)

Source: https://treatyeducationresources.ca/activity-1-sharing-and-showing-respect/

Discussion Questions:

- Leroy] Little Bear (Niitsitapi / Blackfoot) writes in “Jagged Worldviews Colliding” that the function of Indigenous law (what he calls “Aboriginal values and customs”) “is to maintain the relationships that hold creation together”.

What insight does Ginnish’s story demonstrate about Indigenous law?

Activity 2

- As a class, view the short video Indigenous Voices on Treaties with Maurice Switzer, Bnesi of Alderville First Nation (Ontario). How does the video add to your understanding of Indigenous-Crown/Canada treaties? What connections are you making? What questions require further research?

Understanding the Origins of the Dish With One Spoon Wampum

“The symbolism [of the Dish With One Spoon Wampum] was you never take more than you need and you always make sure there is something left for the next person.”

-Lorrie Gallant, The Dish with One Spoon Wampum.

Wampum Belt (courtesy Canadian Museum of History/575-620)

As described by Well Living House, The Dish With One Spoon Wampum is a “mutually beneficial [agreement]” that “was designed to create peaceful hunting conditions for nations in close proximity to each other.”

"The Dish With One Spoon Wampum uses purple and white beads that represent friendship and peace. The purple 'dish' represents the Continent (Turtle Island) and all the different Nations. The white centre represents the tail of a beaver, or the resources of Turtle Island. Nations are only to eat from the dish with one spoon, meaning that resources should be shared, each territory should be respected and nations will not war with each other for the domination of the resources. This is symbolized by removing the presence of a knife with the dish and spoon.

While The Dish with One Spoon was established long before settlers arrived, it was expected that everyone that came to the region would abide by its rules and acknowledge the existence, history and integrity of the agreement. Instead of a shared commitment to the land, settlers conquered and took ownership over the land and its resources. This is an ongoing living agreement."

- Lorrie Gallant

Connection Questions:

- How does The Dish With One Spoon Waampum help us understand how Indigenous peoples:

- Regard nature and their surroundings?

- Value the land and what it has to offer?

- View how each nation should treat the land and all that it provides? - What does The Dish With One Spoon Waampum teach us about the understood agreements between different Indigenous groups?

Activity 3

Here we explore the way British leaders viewed the agreements they made in the 18th century. The values and principles are exemplified through the principle of “the honour of the Crown.”

“The honour of the Crown is not a written rule, but rather a concept developed by the judiciary based on British notions of noblesse. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, the concept’s role in Aboriginal law dates back to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which states that Indigenous peoples “live under … [the Crown’s] protection.” … The honour of the Crown also seeks to further reconciliation. In all its dealings with Aboriginal peoples, from the assertion of sovereignty to the resolution of claims and the implementation of treaties, the Crown must act honourably.

This principle, the honour of the Crown, gives rise to different obligations under different circumstances.”

Source: https://www.constitutionalstudies.ca/2021/08/honour-of-the-crown/

For additional resources, that outline the understanding of treaties held by British leaders, see Treaty Niagara (1764), Royal Proclamation 1763 PS- Royal Proclamation also available as a primary source text here: the Royal Proclamation

Connection Questions

- How did Europeans view agreements?

- How are these views different from those of Indigenous peoples?

Note: Special thanks to Professors John Borrows and Hamar Foster for their review and additions on treaty making among West Coast First Nations outlined in the opening notes.

Day 3- Broken Promises: What Happens When You Avoid Paying?

Treaties are living documents because the people and their descendants are still here today. Yet we have many examples of treaties that have not been honoured and have remained in dispute for generations. The conflict around the land of Six Nations has sat with the federal government since the time of John A MacDonald, the very first minister of Indian affairs. The Robinson Huron Treaty of 1850 has been locked in a decades long court battle and the cost for past annuities has only just been calculated.

The costs associated with not honouring treaties is extensive. For Indigenous communities, there is the loss of access to lands, living beings and the physical environment that has sustained communities and defined civilizations and cultures since their beginning. The costs of fighting in court are shared by both sides, but for Indigenous communities it is more dear as these communities have less monetary resources to offer lawyers, and every dollar spent could go instead toward community support. And in cases where Canada overrides a community's inherent rights to decide how their land is used, there are large costs involved in keeping police forces in the field, as in both Wet’suet’en and 1492 Land Back Lane land defence sit-ins.

Going all the way back to MacDonald, many of these issues could have been settled out of court through negotiated settlements. The original treaties demonstrate that when we sit down to talk and take into consideration the needs of both sides, we can arrive at settlements that allow for peace and prosperity. In this lesson we will examine the ramifications of long drawn-out court battles and the costs associated with protest and standing up for the community and protecting the land for future generations.

Activity 1

- Using the jigsaw teaching strategy, students can be divided into two expert groups to research and respond to the discussion questions below, then meet in pairs or groups of 4 to share their learning.

Unsettled Cases Study

Group 1

- Land Back Lane Protest - Broken Promises

CASE- LAND BACK LANE

CASE- LAND BACK LANE (SKYLER WILLIAMS) PARDON

Group 2

2. Wet’suwet’en Land- Criminalization of Defenders

CASE- Wet’suwet’en Conflict archives

CASE- Wet’suwet’en Land Explained

Discussion Questions

- Who is involved in this case?

- What TREATY OR PURCHASE is this case related to (if a treaty applies)?

- Who was involved in negotiating the treaty?

- (How) are the perspectives and demands of each group connected to treaty or purchase agreements?

- Were there any protests or other challenges connected to this treaty?

- Are there any additional legal issues/cases/events connected with this case?

- What do you think should happen to satisfy all groups involved?

Debrief

- Ask students to reflect on their learning on these two cases using the S - I - T (Surprising, interesting, troubling) strategy or the Head, Heart, Conscience teaching strategy as a guide for a whole class debrief of the learning, sentiments and questions these cases raise.

Additional Teacher Notes

The basis for Crown and later Canadian (and American) claims to sovereignty over Indigenous peoples’ lands are based on the Doctrine of Discovery - this Doctrine only named land as territory that could be claimed, thus waters are unsettled and disputed and none are included in treaties.

Day 4- Moving Forward in Good Relationship

The treaty making process in Canada has been slow since the Williams Treaties were signed in 1923. While 12 treaties were signed between 1871 and 1923, no more were signed until the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement of 1975 (considered the first modern land settlement).

Treaty making has been slow to progress and with each new treaty, Indigenous peoples have pushed for more clarity in the documents that follow face-to-face meetings and agreements. Hindsight is 20/20, and Indigenous people have learned from the past. This has meant that modern treaties are much heftier documents and take longer to negotiate.

Whether it's the Nisga'a Treaty of 2000, or the creation of Nunavut in 1999 by act of parliament, these agreements all represent complex promises about land use, access, and sharing between different groups of people. Even in recent settlements, treaties vary because they are made at different times, under different circumstances, and in relation to distinct areas of land and people.

This final lesson invites students to view historic nation-to-nation treaties and a contemporary treaty, the Robinson Huron Treaty, as a case study that can guide our future actions and prompt dialogue on what it means to live in good relations with each other.

Resources:

- Document: Robinson Huron Treaty Rights

- CBC Article: Canada, Ontario reach historic $10 billion proposed First Nations treaty settlement

Video: Richard Hill (Tuscarora, Six Nations of the Grand River)

Activity 1: Introducing the Robinson Huron Treaty

1) As a whole class, read aloud the "Introduction" to the Robinson Huron Treaty, and explore the Robinson Huron Treaty map to familiarize students.

Activity 2: Closer read of the Robinson Huron Treaty Document

1. Introduce the titles for each of the next series of readings to give students an overview of what they will be reading next. Set up each of the reading sections below for a Big Paper gallery walk.

2. Students will go through the gallery walk in groups of 2-4 having ‘silent conversations’ on each document. You may opt to assign questions to support students if they are unfamiliar with the big paper strategy, i.e. as you read, note 3 significant facts, 2 questions or words you would like clarification on, 1 comment or connection you are making between your reading and our prior lessons or current issues

- Group 1: pg. 3, "What is a Treaty?"

- Group 2: pgs. 5-6, "Elements of the Treaty" and "Issues of Concern"

- Group 3: pg.7, "Post Treaty"

- Group 4: pg. 10, "Modern Problems"

- Group 5: pgs. 11-12, "Conclusion"

- Group 6: Settlement Article, "Canada, Ontario reach historic $10billion proposed First Nations treaty settlement"

3. Students return to their home group for an out loud discussion, followed by a whole class debrief.

Activity 3

4) As a class, watch the Historica Canada Voices from Here video featuring Richard Hill (Tuscarora, Six Nations of the Grand River), (13 minutes) and have students reflect and respond either in their journal or in an exit card, using our "Connect, Extend, Challenge" strategy.

CONNECT: How do the ideas and information in this video connect to what you already know about treaties between Canada and Indigenous People?

EXTEND: How do the video and Robinson Huron case study extend your understanding of how Canada and Indigenous People can move forward in good relations? How do these texts extend your thinking about why renewed agreements are important to a shared vision for peace, honesty, mutual respect and friendship?

CHALLENGE: What challenges do we face, and how can we begin to meet these challenges to achieve a shared vision for peace, honesty, mutual respect and friendship?

On November 7-8, 2023, the Supreme Court of Canada will hear the proper approach to the interpretation and implementation of the Crown's promise to increase annuity payments to the Anishinaabe Treaty beneficiaries under the Robinson Huron and Robinson Superior Treaties. To read about this significant update, click here, or follow the hearing Restoule Treaty Annuities Litigation, live the Supreme Court website hearing here beginning at 9:30am ET.