If you have ever travelled to Brantford Ontario Canada, you might have been excited to visit the home of Alexander Graham Bell to learn about the invention of the telephone. You might have come for a hockey tournament and had the privilege of meeting Hockey Legend Wayne Gretzky’s father Walter, who loves hanging out at the rinks. You may have picked up brochures with beautiful pictures of the Grand River or did research about Joseph Brant, who was the negotiator between the Mohawk and British during the American Revolution. But you might not know that Brantford is the home of the first residential school in Canada; that the building still stands with the names of children carved into the bricks and that it is one of the few residential school buildings still standing in Canada.

Image of Woodland Cultural Centre courtesy of Six Nations Tourism

Image of Woodland Cultural Centre courtesy of Six Nations Tourism

It’s not a place that a family chooses for their vacation unless they’ve discovered their grandmother was a student or their parents need to go back, just to see it, just to make sure it really happened. And when they finally find the courage to stand on the grounds and walk the halls of a place that brought so much sadness and pain, they’ll never forget this place, nor should anyone else.

The Woodland Cultural Centre

I worked at the Woodland Cultural Centre in Brantford for 11 years as the Education Coordinator. It once was the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School. During these years I’ve met many residential school survivors, as well as their children and grandchildren. I’ve taken them on tours, answered their questions, asked questions, sat with them and cried with them. There is nothing more powerful than the human story. When schools and educators came to the Centre I would say, “I’m not a historian, but I will tell you the story of history.”

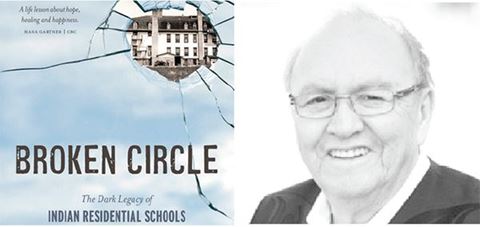

Image of Theodore Fontaine and Broken Circle courtesy of MITT

Image of Theodore Fontaine and Broken Circle courtesy of MITT

Chief Theodore Fontaine, former residential school student and author of Broken Circle: The Dark Legacy of Indian Residential Schools, said in an interview, “How do I honour my roots without aggression? I need to allow the lingering of trauma to guide me, not bury me.”

Indigenous people are never going to get over this. We will always remember, and always be reminded, because it is our lived experience.

Honouring Residential School Survivors: A Postcard to a Survivor

The stories are difficult to share but each time I do I’m reminded of resilience more than trauma. I want Canada to see First Nations people as strong and resilient and to see that residential school survivors, who survived their pasts, still have hearts filled with love for their families and community. I want Canadians to have the courage to bare witness to these stories, then stand in solidarity and participate in a future of hope and healing.

The idea of my postcard activity began when a woman came to the Centre with a box of old postcards she had found in her grandmother's attic. She read through them and realized they were written between two girls who had attended the Mohawk Institute Residential School. They had become friends but were separated, as one was sent to a foster home and the other remained at the school. I could not forget about these postcards and I needed to find a way to honour them.

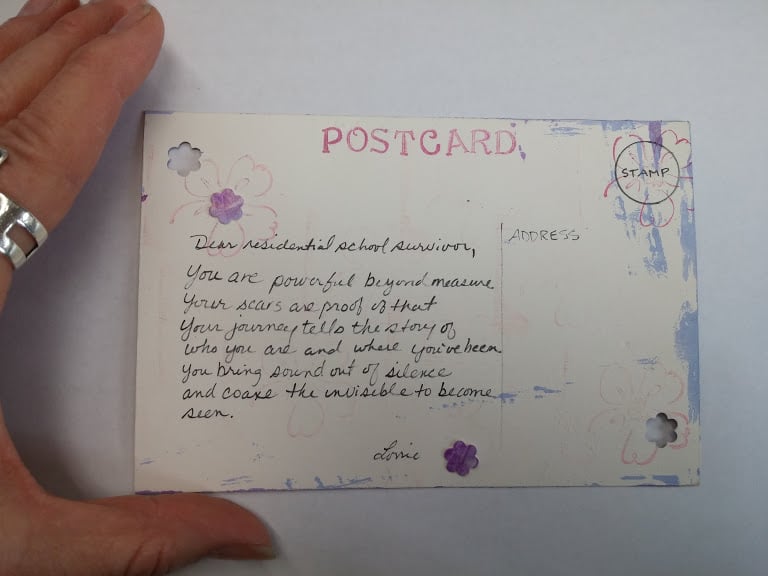

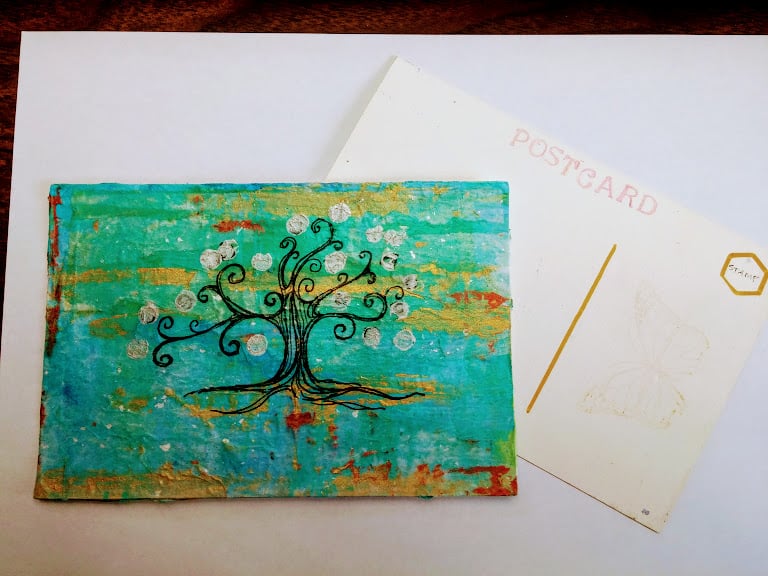

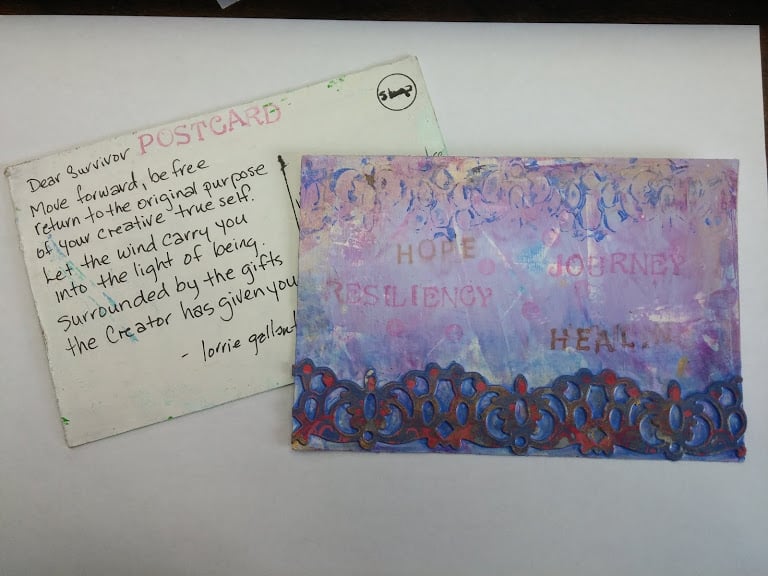

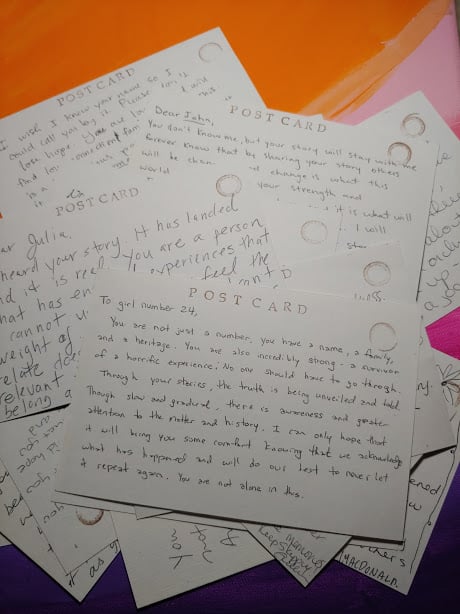

In my presentations on Residential Schools, I decided to give participants information on the children that had attended the Mohawk Institute. I ask them to embrace a single child and learn something about them- what their number was, what First Nations community they came from, whether they had siblings, or whether something happened to them while they attended the school. It provides a connection. At the end of the presentation, I then ask participants to write a message to the child they’ve come to know. A postcard is just a 4x6” paper and it is not too overwhelming and just enough space to share a few words. On the opposite side I suggest creating a small piece of art to express how they feel. Depending on where I am, I ask them to attach it to a tree and let the wind take the message, other times I’ve delivered them directly to survivors.

This let go art has become a mindful action that allows processing and the honouring of survivor stories in a little space in our hearts. I think this relates to the lingering of trauma that Theodore Fontaine spoke of, so that it will guide us, not bury us.

Reconciliation is when we recognize, acknowledge and respond from a place of compassion and empathy.

Participants write messages to students who attended Mohawk Institute Residential School. While some had information like a name to address their postcards, others were only provided a student number.

Participants write messages to students who attended Mohawk Institute Residential School. While some had information like a name to address their postcards, others were only provided a student number.