In this blog post you will find practical ideas, gain key understandings and uncover fascinating histories that will inform and enhance your capacity to teach Chinese Canadian narratives through an anti-racist approach in this two-part blog series by researcher, educator and historian of Chinese people in Canada, Timothy J. Stanley

Over the past 4 years, the rise in targeted violence, discrimination and social exclusion of Asian Canadians raised anxieties about the precariousness of safety, inclusion and belonging for members of these communities. At a time when many were reflecting on the 2023 centenary of Canada’s ban on Chinese immigration and forced identity registration, it became undeniable that in spite of the progress attained, mythologies of perpetual unbelonging and inherent peril persisted; this was the danger in the telling of Canadian history, scrubbed of affirming Chinese Canadian narratives (an erasure familiar to other equity and justice seeking groups).

Rising discrimination prompted new spaces to open up for educators, museums, artists and activists to fill in missing pieces of our historical tapestry in specific and intersectional ways. Our hope for strengthening historical understanding, and honouring Chinese histories that invite joy, pride, curiosity and understanding informed our invitation to Timothy Stanley and educator Jse-Che Lam to contribute to FacingCanada. We are deeply appreciative of their time, expertise and work. We hope you find the inspiration, connection and practical ideas as you read on.

Reflections on Teaching Chinese Canadian Histories (Part I)

Timothy J. Stanley

University of Ottawa

-3.png?width=350&height=270&name=unnamed%20(4)-3.png)

Chinese people have been in what is today Canada since before the country existed, but can still be seen as threatening aliens, foreigners who do not belong. Understanding how the Chinese have been excluded historically, helps us to understand how present-day racism works. Bringing this knowledge into our classrooms can help all of our students see themselves in what we teach. While I consider myself to primarily be an antiracism educator, I focus on Chinese Canadian history both to understand the dynamics of racist exclusion and to address my own family’s history.

1. Explicitly Teach about the Diversity within any Group: All Chinese people Are Not Alike

The 1.7 million Chinese people in Canada today are not a single group; they are many different communities, each with very different histories. These groups are shaped by many things including when people or their ancestors arrived in Canada (last week or in the nineteenth century), under what circumstances (refugees or free immigrants), from where (e.g., Northern China, Guangdong Province, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Great Britain), and what their home language is (English, French, Mandarin, Cantonese, Toisanese, Vietnamese, etc.). Chinese Canadians consequently do not share the same history, but all students, whether Chinese or not, need to know something of the Chinese presence in Canada, and their fight for human rights and equality.

2. Begin with Canada’s long held, long valued ties with China and East Asia

-2.png?width=512&height=406&name=unnamed%20(5)-2.png)

The launch of the North-West America at Nootka Sound, (a fur trading fort built by Chinese workers) 1788. From Meares's Voyages. John Meares, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Canadians take for granted ties with Europe. Yet, connections to China first brought Europeans to Canada. Explorers did not set out to “discover” Canada; they were looking for a route to China and the Far East. Canada has a west coast because of the triangular sea otter trade between England, the Pacific Coast and China. The sailing vessel and fur trading fort that Chinese workers built on Nootka Sound in 1788 established the British claim to the territory. The Canadian Pacific Railway may have welded the country together, but it would not have been completed without Chinese workers, while the China trade paid for it. Today, we commonly eat Chinese food, use cell phones and computers assembled in China, and Chinese inventions such as the printing press and the compass shape our world.

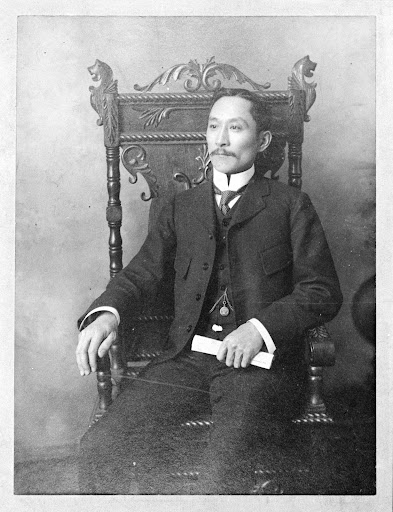

Photograph of Won Alexander Cumyow 金有, circa 1900.

(City of Vancouver archives, AM1523-S6-F54-: 2008-010.2280)

3. Begin from the Beginning: Chinese communities are older than Canadian Confederation

The Chinese communities of Canada date back continuously to the 1858 Fraser River Gold Rush in British Columbia and the founding of the Victoria, BC, Chinatown. At the time, Canada was little more than the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes valleys (Upper and Lower Canada). When the Chinese first arrived there were at most a few hundred non-Indigenous people (almost all employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company) in BC and, except for some coastal areas, Indigenous people controlled the territory. The first Chinese Canadian, Won Alexander Cumyow (金有, meaning “having gold”), was born at Fort Harrison, BC in 1861, ten years before BC joined Canada. Like other Chinese, he enjoyed close relations with First Nations people, and grew up speaking Chinook, the Indigenous trade language, as well as English, Cantonese, and his parents’ Hakka.

4. Understand how anti-Chinese and interconnected racisms were tied to settler colonialism

The whole point of British and Canadian settler colonialism has been to convert the territories of Indigenous people into the private property of people from Europe, preferably from Britain, and of their Canadian-born descendants. The British and Eastern Canadian colonizers of BC saw Chinese people as competitors for dominance. After Confederation, they ensured their dominance by keeping the Chinese and Indigenous people out of government, taking the right to vote away from both groups. At the time, First Nations were the overwhelming majority with a population at least five times larger than that of white settlers, and the Chinese may have been the next largest group of adult men. Other legislation blocked both groups from claiming (i.e., pre-empting) land seized from First Nations. Over two hundred pieces of BC legislation, one out of every ten acts passed in the province’s history, discriminated against the Chinese, barring them from democratic rights, controlling where they could work, and the work they could do. Often the same laws also discriminated against First Nations people, and later against Japanese people and South Asians. By the early twentieth century racist violence had closed entire districts to the Chinese and other Asians.

In 1885, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald extended Chinese exclusion to the federal level. While creating a federal polity of property-owning men, i.e., defining who government was of, for and by, he blocked all “persons of Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting for fear that the Chinese would control the vote in BC. He also implemented the head tax on the immigration of Chinese workers and their families. The head tax, initially set at $50, was raised to $500 dollars (more than a year’s wages at the time) in 1903. Between 1923 and 1947, the government banned Chinese immigration outright and required all Chinese in Canada, including Canadian-born citizens, to register with the federal government and carry their registration certificates at all times. The Chinese Immigration [Exclusion] Act subjected those who failed to produce a certificate on demand to fines and imprisonment, and, in the case of the foreign born, deportation. From the act’s coming into effect until it was repealed in 1947, only 44 people of Chinese origins were allowed to immigrate to Canada. These included the two-year-old Adrienne Poy, a.k.a. Adrienne Clarkson, the 26th Governor General of Canada, a refugee from Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. Only the act’s repeal prevented her family’s deportation. The Chinese are the only group to whom such measures applied.

This is the first post in a two part series. Part II Coming Soon.

-3.png?height=100&name=unnamed%20(4)-3.png)